Illicit economies in Mozambique’s embattled Cabo Delgado: answering the key questions.

Just over a year ago, the town of Palma, Cabo Delgado, was the target of a major insurgent attack that left dozens dead. A mass exodus of thousands of survivors fleeing the town by boat sought refuge in Pemba, the provincial capital further to the south.1 The attack caught international attention in part due to Palma’s proximity to the US$20 billion gas development run by French oil company Total, on the Afungi peninsula.

A year on, South Africa is on the cusp of sending a full combat force to the Southern African Development Community (SADC) regional deployment (known as SAMIM) operating in Cabo Delgado,2 while the SADC itself has extended the mandate of SAMIM to July 2022, supposedly for a phase of ‘de-escalation’ of the conflict.3 When SAMIM and Rwandan forces first arrived in June 2021 and recaptured swathes of insurgent-held territory, it initially seemed that the tide of the conflict had turned. Now, however, violence continues to flare up as smaller, more scattered groups of insurgents – known locally as al-Shabaab – are terrorizing populations.4

In Nangade district, which borders Tanzania, 24 000 people were forced to flee their homes between January and mid-March 2022, according to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). Some 5 000 more have fled to Mueda, a neighbouring district. ‘Those fleeing violence suffered and witnessed atrocities, including killings and the decapitation and dismemberment of bodies, sexual violence, kidnappings, forced recruitment by armed groups and torture. The threat of renewed violence means that the number of people arriving in Mueda continues to increase,’ said UNHCR spokesperson Boris Cheshirkov.5

Around 784 000 people have been displaced since the conflict started in October 2017, according to the latest data released by the International Organization for Migration.6 Efforts to return displaced people to Mocímboa da Praia – a strategically important town in restoring the region’s economy – are stalling, because the area is still insecure.7

As the rainy season — which gave al-Shabaab insurgents a chance to regroup — nears its end, there are fears of a renewed escalation in the conflict, and potential expansion into the neighbouring Niassa and Nampula provinces. The violence has waxed and waned according to seasonal cycles in previous years.

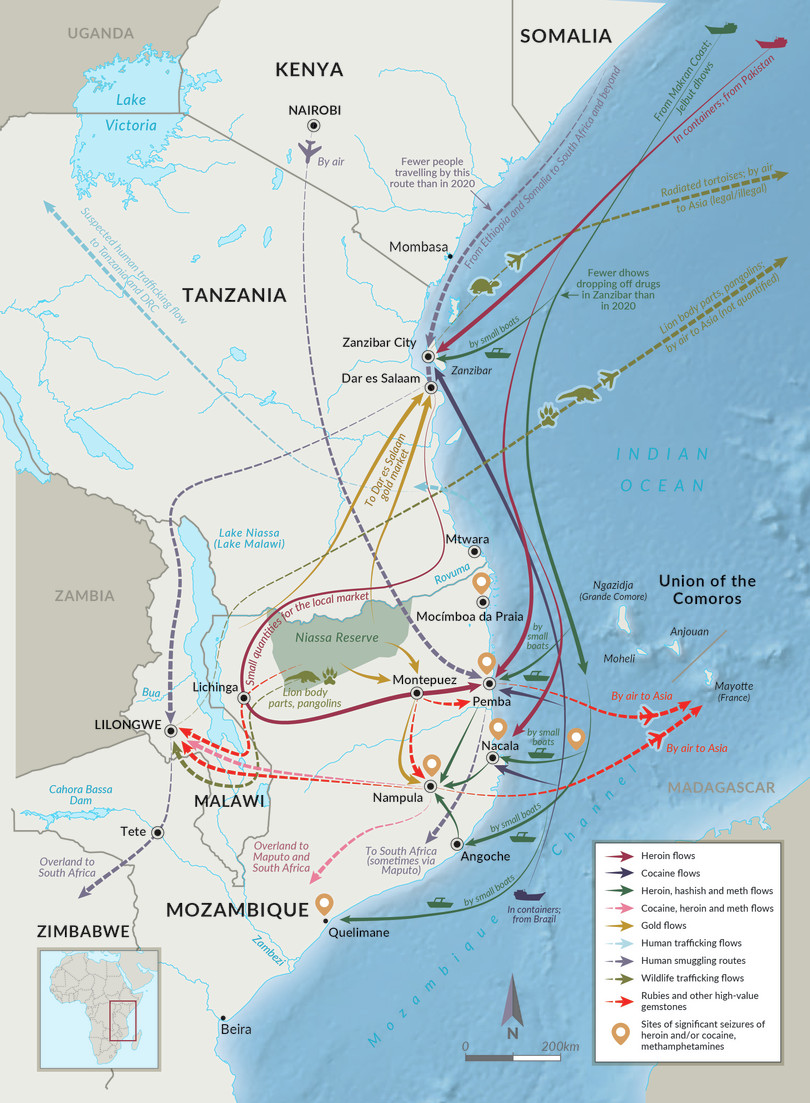

But what impact could this resurgence of violence have on the illicit economy? The region has long been a key economic corridor for illicit flows that traverse the East African coast, including drug trafficking (chiefly of heroin and, more recently, methamphetamine and cocaine); illicitly exported timber, ivory and other wildlife products; and smuggled gems and gold. The question of whether al-Shabaab is involved in or controls illicit economies has been the subject of intense speculation, politically driven allegations and, at times, disinformation. Our research has investigated key questions about how illicit economies play a role in the political economy of this troubled region.8

Do illicit economies fund the insurgency?

Overall, our research has concluded that involvement in the illicit economy constitutes only a small proportion of the insurgents’ funding base. The main sources of funding for the insurgency are local, primarily obtained from the support of local businesspeople, cash and goods seized during attacks, and looting.

Some new evidence has emerged of alleged international support to the insurgents. In March 2022, the US enacted sanctions against four alleged financiers of the Islamic State, all of whom are based in South Africa. The Mozambican insurgents have claimed allegiance to the Islamic State since 2019. One – Peter Charles Mbaga – is accused of having supported the insurgents by helping the group acquire equipment from South Africa and attempting to procure weapons for them in Mozambique.9 However, local sources of funding appear to be the group’s primary support.

In terms of illicit economies, GI-TOC research and interviews have found no current connection between drug trafficking and al-Shabaab. When the conflict broke out, traffickers based in Mocímboa da Praia shifted their operations to the south, away from the conflict’s epicentre. These traffickers have yet to return to their former northern bases, as the security situation remains volatile.

The discovery of 28 kilograms of heroin in Mocímboa da Praia in early October 2021 was taken by Mozambican authorities as evidence that al-Shabaab is involved in drug trafficking,10 as the drugs were discovered in a location known to be used by the group during its occupation of the town. However, other factors – such as the time of year of the seizure, the volume of drugs involved and the location – suggest that this cache of drugs had, in fact, been stored by another trafficker before the insurgents captured Mocímboa da Praia. The trafficker likely then abandoned the drugs in an urgent escape. To our knowledge, no other similar seizures have been made.

Kidnap for ransom – of both Mozambican and foreign nationals – is a source of income for al-Shabaab. A standard opening ransom demand from the insurgents is apparently 1 million Mozambican meticais (US$16 000).11

This is part of a broader, well-documented al-Shabaab strategy of kidnapping people in towns and villages under attack. The insurgents kidnap individuals with skills they wish to exploit – such as medical professionals – young children to train as fighters, and women and girls.12 Human Rights Watch estimated in December 2021 that more than 600 women and girls have been kidnapped by al-Shabaab since 2018.13 Once inside the insurgent bases, these young women are reportedly taught to behave as part of al-Shabaab’s Islamist social order and are forced into ‘marriages’ to al-Shabaab fighters.14

It is suspected that select groups of younger women are then trafficked by the insurgents. Women who had previously been held captive by the insurgents reported to Mozambican think tank Observatório do Meio Rural that some of the kidnapped women were ‘selected’ to go to Tanzania to study English.15 Sources suggest that these women and girls are, in fact, trafficked overland from the insurgent-controlled areas to southern Tanzania.16 Their subsequent fate remains unknown. There are initial reports that young men and boys are trafficked overland to the DRC to work in informal mining to generate money for the insurgency.17 It has not yet been possible for the GI-TOC to independently verify these trafficking flows.

Illicit flows through northern Mozambique

Note: Dashed arrows indicate flows that have been reported to the GI-TOC where precise geographical routes are unknown.

A shipment of heroin and methamphetamine seized in Nacala, northern Mozambique, March 2021.

Photo: SERNIC

Research by the GI-TOC has found no evidence that al-Shabaab has been taxing or controlling northern Mozambique’s illicit gemstone or gold trade. Cabo Delgado’s hotspots of artisanal and small-scale mining and the illicit trade in gold and gemstones are, in fact, concentrated outside of areas where al-Shabaab has held territory.

However, some black-market gold and ruby traders are reported to provide financial support to the insurgents. These are individuals running legitimate businesses in the region as well as smuggling gold and precious gems. They also seem to have been connected to al-Shabaab for several years, perhaps pre-dating the armed conflict in the years when the group was a radical conservative religious sect. These traders allegedly provide a financial network to shift cash, gemstones, gold, people and goods over the boundary lines of the conflict, to launder funds through legitimate business, and to deposit

payments on behalf of the insurgents.

Has the conflict had an impact on illicit economies in Cabo Delgado?

Trafficking routes through northern Mozambique are resilient and have adapted to the conflict, by shifting away from areas where insurgents hold territory and the conflict is most intense. By early 2021, drug trafficking routes had moved south through southern Cabo Delgado and Nampula province and have remained there.

Heroin and cocaine shipped in containers are still arriving at the ports of Pemba and Nacala. Heroin and methamphetamine arriving on Jelbut dhows – long-range wooden fishing and transport vessels – from Iran and Pakistan are being offloaded further south.

Before the conflict, deliveries arrived at Mozambique’s northern coast, with Pemba as the southernmost drop-off point. The beaches, small ports and towns of Quissanga, Ilha do Ibo and Mocímboa da Praia were key hotspots for drug-trafficking activity. The town of Mocímboa da Praia has long been known as a smuggling hub, not just as a landing point for heroin but also for people smugglers ferrying passengers along the ‘southern route’ of migration from the Horn of Africa towards southern Africa, and as a transit point for flows of ivory poached in Niassa Special Reserve, illegal timber and other illicit goods.18 These flows have now been disrupted.

Now, Pemba is the most northerly drop-off point, and drugs are also landing on the coasts of Nampula and Zambezia provinces, including in Nacala, Angoche and Quelimane.19 International law-enforcement sources, people involved in trafficking networks and local fishing communities report that drugs are still arriving at Pemba’s fishing port. Fishing vessels are often used to collect drug shipments from larger vessels out at sea before they are brought to the fishing port and beaches south of Pemba, then warehoused locally ahead of onwards transit.20 Reports suggest that from arrival into Nampula province, heroin and cocaine are now also being transported overland west through Malawi, rather than exclusively southwards to South Africa and Maputo, as in previous years.21

Mozambican authorities seize 82 containers of illegally felled timber bound for China at the port of Pemba, August 2020.

Photo: ANAC

A similar pattern has been seen in the trafficking of illegal timber, which has been a market in northern Mozambique for decades.22 The scale of this trade from Cabo Delgado was demonstrated in August 2020, when Mozambican authorities seized 82 containers of illegally harvested logs bound for China and held them at the port of Pemba. Those containers were later smuggled out from police custody and exported in December 2020.23 Following investigations, 66 of the containers were recovered en route to China.24 In mid-November 2021, a further seven containers were recovered.25

Chinese logging companies dominate the Cabo Delgado logging industry.26 These companies are currently most active along the corridor between Montepuez and Mueda and often operate illegally within the eastern boundary of the Niassa Special Reserve.27 This area, to the west of the main area of insurgent activity, has been secure from al-Shabaab attacks, enabling these companies to continue operating.

While logging had been prominent in this region for many years, it intensified during the conflict, and there were reports of military checkpoints extracting rent payments from logging trucks moving along this road.28

Within al-Shabaab territory, logging activity is reportedly less intensive than in areas controlled by the Mozambican military, though it is ongoing. There are no reports suggesting that al-Shabaab has been involved either directly in the logging trade or in ‘taxing’ the trade systematically as a means of funding. As with drugs, the most intensive illicit-economy activity is outside the insurgents’ areas of control.

Did illicit economies contribute to the outbreak of the conflict?

The insurgency in Mozambique was born from an amalgam of different drivers, principally deep-seated grievances over economic inequality and political exclusion.29 Socio-economic divides fractured communities along religious and ethnic lines. People in Cabo Delgado have borne decades of government neglect and extreme poverty while they have seen political elites seize the benefits of the region’s natural resources – such as rubies and gas – and profiteer from criminal markets.

For decades, the financial gains of northern Mozambique’s illicit economies, including drug trafficking and illegal logging,30 have also accrued with senior FRELIMO figures, the dominant political party in the country, and local business elites.31 Corruption is a characteristic feature of governance in the region. One expert interviewed by the GI-TOC described corruption as the single most important factor shaping Mozambique’s economy.32 Organized criminal activity has, for many years, been a significant driver of this corruption.

These injustices have been used in the insurgents’ propaganda. For example, in Muidumbe in April 2020, insurgent leader Bonomado Omar (also known as ‘Ibn Omar’) addressed assembled residents saying that they had occupied the village ‘to show that the government of the day is unjust. It humiliates the poor and gives advantages to the rich. The people who are detained are from the lower classes and this is not just. Whether people like it or not, we are defending Islam.’33

In the case of illicit gemstones, the management of one illicit economy may have driven insurgent recruitment. Artisanal miners working illegally on private mining concessions have been treated brutally by police and mine security. To these groups, this was perceived as the state – principally through the police – forcing them to abandon their livelihoods in order to protect powerful interests.34 This contributed to radicalization.

Figure 2 Heroin flows from Afghanistan, including via northern Mozambique.

There are long-standing links between artisanal miners of gems and gold and the insurgents. A number of research groups have reported that insurgents have concentrated their recruitment efforts on garimpeiros, as the informal miners are known, by exploiting local grievances over economic marginalization,35 or in some cases by tempting recruits with promises of employment in Cabo Delgado mining sectors.36 This includes recruiting garimpeiros working in Niassa Special Reserve.37 A prominent leader of al-Shabaab, named Maulana Ali Cassimo, is known to have demonstrated publicly against the attitude of authorities to artisanal miners and poachers in Niassa Special Reserve before the insurgency.38

Why understanding illicit economies is important in Cabo Delgado

As seen in claims that the insurgents have been involved in drug trafficking, it is easy to make assumptions about the relationship between conflict and organized crime that turn out to be erroneous. Other contexts, such as the conflict in Afghanistan, can be a cautionary comparative example, as there the relationship between the Taliban and the drug trade was poorly understood or overestimated. This led to wasteful and damaging policy decisions.39 Therefore, in-depth reporting of the dynamics of the conflict is needed to develop a more nuanced picture.

The factors that helped create the insurgency – a breakdown in governance and delivery of government services, socio-economic exclusion, rampant corruption and organized crime, elite capture of resources, and ethnic and religious divides – remain in place in Cabo Delgado. The International Crisis Group, which has been monitoring the conflict, reported in a briefing in February 2022 that with these local grievances unaddressed, ‘the insurgency will persist as a source of regional insecurity.’40 The GI-TOC has drawn the same conclusion from its research. In addition, while trafficking routes have shifted slightly, northern Mozambique remains a key economic corridor for illicit flows, including major drug-trafficking routes to the southern African region and beyond.

Notes

-

Al Jazeera, Mozambique: Thousands flee besieged Palma by boats, 29 March 2021, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/3/29/thousands-flee-besieged-mozambican-town-by-boat. ↩

-

See initial details of the deployment in: Erica Gibson, SANDF deploys Combat Team Alpha to fight Mozambique insurgents, News24, 21 February 2022, https://www.news24.com/news24/southafrica/news/sandf-deploys-combat-team-alpha-to-fight-mozambique-insurgents-20220221; and discussion of the latest status of the deployment in Cabo Ligado weekly, 28 March–3 April 2022, https://acleddata.com/acleddatanew/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/Cabo-Ligado-92.pdf. ↩

-

Opening remarks by the Minister of International Relations and Cooperation, Dr Naledi Pandor, at the Extraordinary Meeting of the Ministerial Committee of the Organ Troika plus the Republic of Mozambique in Pretoria, 3 April 2022, http://www.dirco.gov.za/docs/speeches/2022/pand0403.pdf. ↩

-

Obi Anyadike and Tavares Cebola, Military intervention hasn’t stopped Mozambique’s jihadist conflict, The New Humanitarian, 8 March 2022, https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2022/03/08/military-intervention-has-not-stopped-mozambique-jihadist-conflict. ↩

-

UNHCR Africa, One year after Palma attacks, thousands continue to flee violence in northern Mozambique, 22 March 2022, https://www.unhcr.org/afr/news/briefing/2022/3/623991b34/year-palma-attacks-thousands-continue-flee-violence-northern-mozambique.html. ↩

-

Data available at: https://displacement.iom.int/mozambique. ↩

-

Cabo Ligado Weekly: 21-27 March, 29 March 2022, https://www.caboligado.com/reports/cabo-ligado-weekly-21-27-march-2022. ↩

-

GI-TOC, Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin, Issue 7, 7 May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/esaobs-risk-bulletin-7; GI-TOC, Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin, 17, 28 April 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/esaobs-risk-bulletin-17. ↩

-

US Department of the Treasury, Treasury Sanctions South Africa-based ISIS Organizers and Financial Facilitators, 1 March 2022, https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0616; GI-TOC, From Afghanistan to Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado – the implications of Taliban rule for the southern African drug trade, Daily Maverick, 26 October 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-10-26-from-afghanistan-to-mozambiques-cabo-delgado-the-implications-of-taliban-rule-for-the-southern-african-drug-trade. ↩

-

Club of Mozambique, Mozambique: Heroin seizures suggest insurgents also drug traffickers, 18 October 2021, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-heroin-seizure-suggest-insurgents-also-drug-traffickers-202975. ↩

-

Investigative report: The nuances of transboundary trafficking in firearms, women and mineral resources specific to northern Mozambique, submitted by Arlindo Chissale to the GI-TOC, 7 November 2021, unpublished. ↩

-

João Feijó, Characterization and social organization of Machababos from the discourses of kidnapped women, Observatório do Meio Rural (OMR), April 2021, https://omrmz.org/omrweb/wp-content/uploads/OR-109-Characterization-and-social-organizacion-of-Machababos.pdf. ↩

-

Human Rights Watch, Mozambique: Hundreds of women, girls abducted, 7 December 2021, https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/12/07/mozambique-hundreds-women-girls-abducted. ↩

-

Investigative report: The nuances of transboundary trafficking in firearms, women and mineral resources specific to northern Mozambique, submitted by Arlindo Chissale to the GI-TOC, 7 November 2021, unpublished. ↩

-

Interview with OMR researcher João Feijó, Maputo, 5 October 2021. ↩

-

Investigative report: Pemba, Montepuez and Negomano, submitted by Omardine Omar to the GI-TOC, 9 October 2021, unpublished. ↩

-

Interview with OMR researcher João Feijó, Maputo, 5 October 2021. ↩

-

Alastair Nelson, A triangle of vulnerability: Changing patterns of illicit trafficking off the Swahili coast, GI-TOC, May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/triangle-vulnerability-swahili-coast. ↩

-

Current information suggests that dhow-based drug deliveries are occurring around Nacala and Quelimane again. Interview with Mozambican law-enforcement official, 11 January 2022, via WhatsApp; interview with Mozambican journalist, 13 January 2022, via WhatsApp. ↩

-

Investigative report: Pemba, Montepuez and Negomano, submitted by Omardine Omar to the GI-TOC, 9 October 2021, unpublished. ↩

-

Interview with international law-enforcement source, Maputo, 5 October 2021. ↩

-

Alastair Nelson, A triangle of vulnerability: Changing patterns of illicit trafficking off the Swahili coast, GI-TOC, May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/triangle-vulnerability-swahili-coast. ↩

-

Environmental Investigation Agency, Shipping industry: Where there is a will there is a way, 26 May 2021, https://eia-global.org/press-releases/20210527-containers-of-stolen-illegal-timber-return-to-mozambique. ↩

-

Mozambique News Agency, Mozambique: Three more containers of stolen timber recovered, AllAfrica, 27 July 2021, https://allafrica.com/stories/202107270743.html. ↩

-

Club of Mozambique, Mozambique: Illegally exported timber recovered, 16 November 2021, https://clubofmozambique.com/news/mozambique-illegally-exported-timber-recovered-204690. ↩

-

While many companies operate with legal concessions to harvest logs, this becomes illegal trade when the volumes and species harvested go outside legal bounds, and when unworked logs are exported from Mozambique. ↩

-

Interview with senior wildlife official from Niassa Special Reserve, 7 October 2021. ↩

-

Interviews with conservationists working in Niassa Special Reserve, 7–10 October 2021; GI-TOC, Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin, 17, 28 April 2021, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/esaobs-risk-bulletin-17. ↩

-

Eric Morier-Genoud, The jihadi insurgency in Mozambique: Origins, nature and beginning, Journal of Eastern African Studies, 14, 3, 2020, 396–412. DOI: 10.1080/17531055.2020.1789271. ↩

-

Richard Poplak, IS-land: Has the age of southern African terrorism properly begun?, Daily Maverick, 4 May 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-05-04-islamic-state-land-has-the-age-of-southern-african-terrorism-properly-begun; Ashoka Mukpo, Gas fields and jihad: Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado becomes a resource-rich war zone, Mongabay, 26 April 2021, https://news.mongabay.com/2021/04/gas-fields-and-jihad-mozambiques-cabo-delgado-becomes-a-resource-rich-war-zone. ↩

-

Joseph Hanlon, The Uberization of Mozambique’s heroin trade, London School of Economics, July 2018, https://www.lse.ac.uk/international-development/Assets/Documents/PDFs/Working-Papers/WP190.pdf; Simone Haysom, Where crime compounds conflict: Understanding northern Mozambique’s vulnerabilities, GI-TOC, 2018, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/northern_mozambique_violence. ↩

-

Interview with Institute for Security Studies (ISS) consultant Borges Nhamirre, Maputo, 6 October 2021. ↩

-

GI-TOC, Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa Risk Bulletin, Issue 7, 7 May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/esaobs-risk-bulletin-7. ↩

-

Interview with Adriano Nuvunga, CDD, Pemba, 15 October 2021. ↩

-

Gregory Pirio, Robert Pittelli and Yussuf Adam, The emergence of violent extremism in northern Mozambique, Africa Center for Strategic Studies, 25 March 2018, https://africacenter.org/spotlight/the-emergence-of-violent-extremism-in-northern-mozambique. ↩

-

Salvador Forquilha and João Pereira, After all, it is not just Cabo Delgado! Insurgency dynamics in Nampula and Niassa, Instituto de Estudos Sociais e Económicos, 11 March 2021, https://www.iese.ac.mz/ideias-n-138e-sf-jp. ↩

-

Interview with OMR researcher João Feijó, Maputo, 5 October 2021; interview with senior wildlife official from Niassa Special Reserve, 7 October 2021. ↩

-

João Feijó, From the ‘faceless enemy’ to the hypothesis of dialogue: Identities, pretensions and channels of communication with the Machababos, OMR, 10 August 2021, https://omrmz.org/omrweb/wp-content/uploads/DR-130-Cabo-Delgado-Pt-e-Eng.pdf. ↩

-

GI-TOC, From Afghanistan to Mozambique’s Cabo Delgado – the implications of Taliban rule for the southern African drug trade, Daily Maverick, 26 October 2021, https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-10-26-from-afghanistan-to-mozambiques-cabo-delgado-the-implications-of-taliban-rule-for-the-southern-african-drug-trade. ↩

-

International Crisis Group, Winning Peace in Mozambique’s Embattled North, Africa Briefing 178, 10 February 2022, https://www.crisisgroup.org/africa/southern-africa/mozambique/b178-winning-peace-mozambiques-embattled-north. ↩