What the chequered history of the ‘Somali 7’ fishing fleet tells us about the political economy of IUU fishing in Somalia.

The waters off Somalia are some of the richest fishing grounds in the world. Following the steady decline in attacks by Somali pirates since 2012, foreign fishing fleets have gradually returned to Somali waters. Many of these, particularly those originating in Iran, Yemen and South East Asia, routinely engage in IUU (illegal, unreported and unregulated) fishing practices.

Over four decades of civil war, Somalia has balkanized into a series of semi-autonomous regional administrations, loosely overseen by a federal government located in the capital of Mogadishu, and one breakaway region, Somaliland. State institutions are extremely weak and corruption is widespread. Relations between the central Federal Government of Somalia (FGS) and the regions have often been fraught, and the FGS and regional administrations have repeatedly entered into separate and often conflicting contractual agreements with foreign entities. Fishing licences and other permissions issued by one local Somali authority are often not recognized by another. These tensions have further heightened the political risk of doing business in Somalia for potential foreign partners.

Domestically, the prevalence of foreign IUU fishing vessels has been frequently cited as a justification for acts of piracy by Somalia-based gangs,1 who present themselves as defenders of Somali waters against foreign exploiters.2 However, the reality is far more complex. Foreign IUU fishing operations are frequently facilitated by local Somali agents, often in cooperation with government or quasi-governmental actors, who for a fee provide fishing licences, flag registrations, falsified export documentation and even armed onboard security detachments.

The Somali 7

A prominent example of such facilitation emerged in 2017, when a fleet of seven long-haul trawlers – collectively dubbed the ‘Somali 7’ by investigative journalist Ian Urbina – appeared in fishing waters off Puntland, a semi-autonomous region in north-eastern Somalia.3 The fleet consisted of the trawlers Chotpattana 51, Chotpattana 55, Chotchainavee 35, Chaichanachoke 8, Chainavee 54, Chainavee 55 and Supphermnavee 21. Onboard were 240 Cambodian and Thai crewmembers, who had been told that the vessels would not be operating beyond Thai waters.4 Urbina’s book The Outlaw Ocean extensively documented the labour abuses and human rights violations committed aboard the Somali 7, including beatings, lack of medical care, human trafficking, death threats and unpaid wages, which took place with the complicity of both Somali federal government and Puntland administration officials.5

While the fleet had re-flagged under the Djiboutian registry in 2016, presumably in order to circumvent newly passed Thai fishing regulations, ownership of the vessels was traced to a prominent fishing family in Thailand headed by former Thai senator Wanchai Sangsukiam.6 Companies affiliated with the Sangsukiam family have long been implicated in IUU fishing practices, as well as labour and other human rights abuses.7

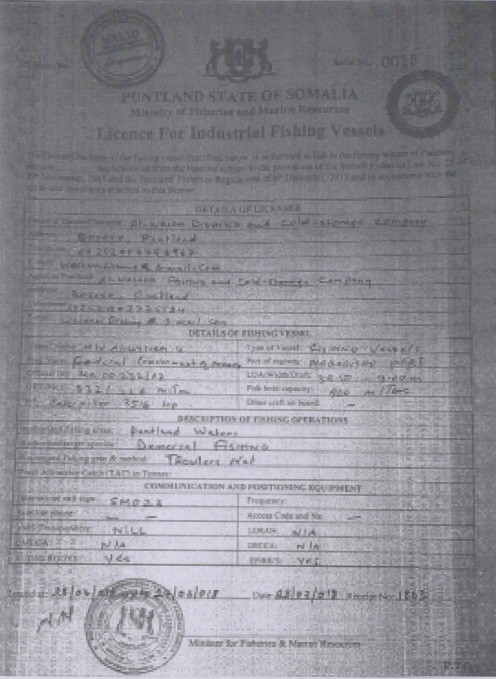

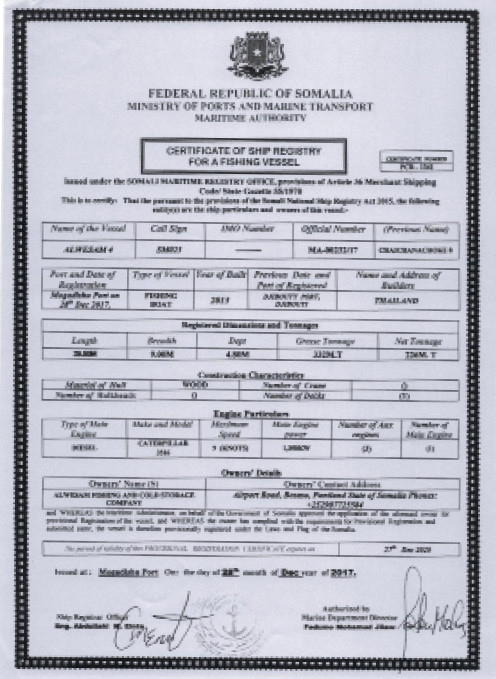

Thai authorities opened an investigation into the owners of the vessels over their IUU practices and the use of trafficked labour. Some of the Cambodian and Thai crewmembers came ashore at the Puntland port of Bosaso and were slowly repatriated between September and November 2017. With the company facing pressure from Thai authorities and having been de-registered by their flag state of Djibouti, in December 2017 four of the vessels were renamed and ostensibly became Somali vessels: the Supphermnavee 21, Chainavee 55, Chaichanachoke 8 and Chainavee 54 became Al Wesam 1, Al Wesam 2, Al Wesam 4 and Al Wesam 5, respectively. The vessels continued to benefit from legal cover and legitimacy from Somali state institutions: not only did the Al Wesam vessels receive Puntland fishing licences, they were also enrolled under the Somali flag registry by the federal Ministry of Ports and Marine Transport.

Puntland fishing licence (left) and Somali flag registration (right) for the Al Wesam 4.

Photo: Indian Ocean Tuna Commission

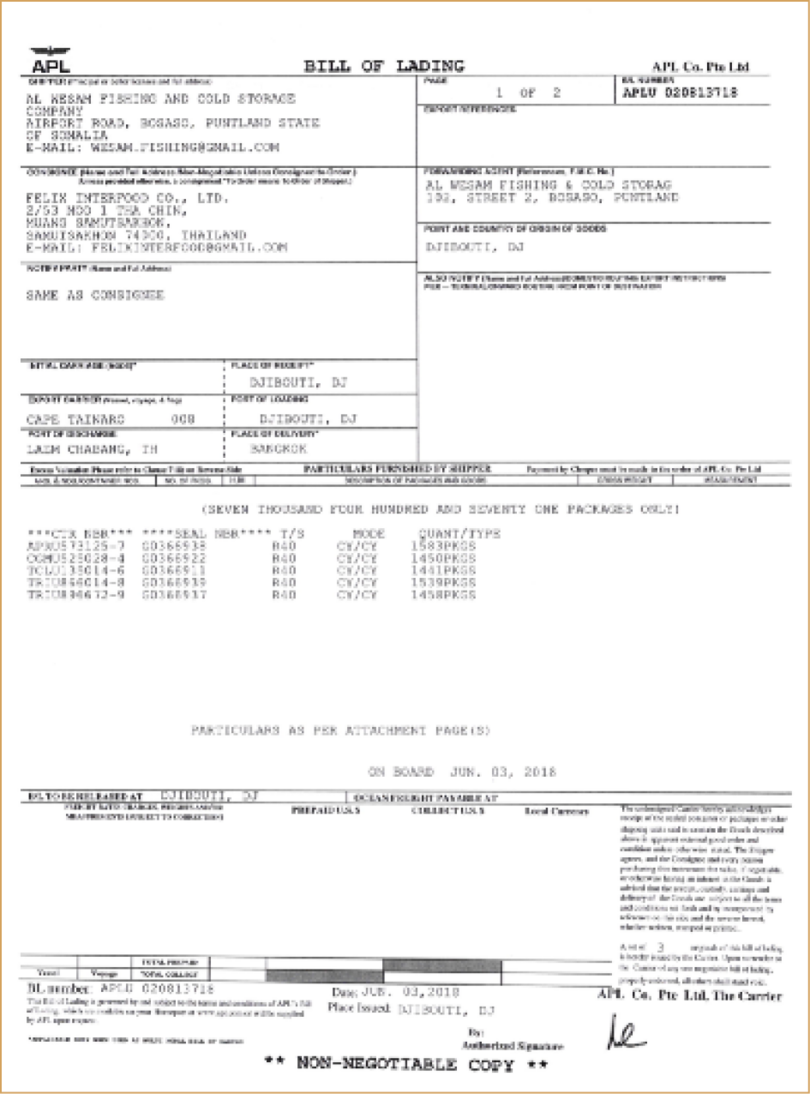

A June 2018 bill of lading for a seafood consignment exported to Thailand by Al Wesam Fishing and Cold Storage Company. The consignee is listed as ‘Felix Interfood Co., Ltd.’

Photo: Ian Urbina, The Outlaw Ocean Project

In keeping with their new Somali identities, the operations of the vessels were transferred to a local front company, Al Wesam Fishing and Cold Storage Company. Based out of Bosaso, Al Wesam Fishing exported the catches from the Al Wesam fleet to Felix Interfood Co., Ltd., a seafood importer in Thailand linked to the Sangsukiam family.8

In June 2018, the operations of Felix Interfood came under scrutiny when Thai authorities questioned the validity of catch and health certificates for 46 containers of the company’s seafood products.9 While the FGS Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources initially attempted to defend the legal status of the Al Wesam vessels, further inquiries from the Thai Department of Fisheries concerning the vessels’ registrations and fishing licences went unanswered.10 Having recognized the Al Wesam fleet as renamed incarnations of four of the Somali 7 IUU fishing vessels, the Thai authorities opted to reject the importation of the 46 containers.11

A new identity and Kenyan crewmembers

Following this importation crackdown by Thai authorities, the Al Wesam 4 underwent another metamorphosis, re-emerging as the Marwan 1 in June 2019.

The Al Wesam 4 (formerly the Chaichanachoke 8) on 18 June 2019 (left), and the renamed Marwan 1 on 28 August 2019 (right). Both photographs were taken close to the littoral town of Qandala. Imagery analysis (shown in the numbering) highlights the similarities between the vessels.

Photo: European Union Naval Force (Somalia)

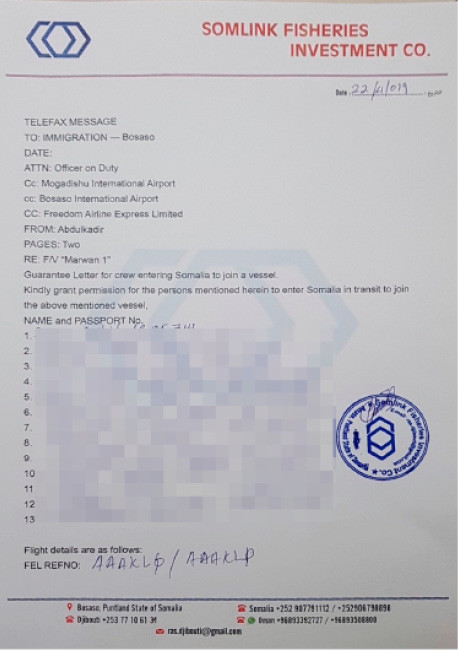

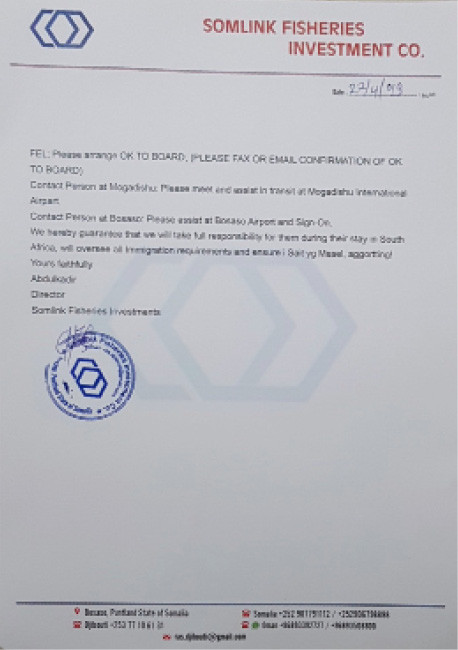

Through Seaport Operations Limited (an unlicensed agency in Mombasa operating in violation of Kenyan law), 13 Kenyan seafarers were recruited to crew the newly christened boat.12 The recruiting agent informed the GI-TOC that he had been contacted in April 2019 by an individual named ‘Abdulkadir’ from a Thai mobile-phone number.13 Abdulkadir subsequently sent the agent airline tickets from Mombasa to Garowe, Puntland, for the 13 crewmembers via WhatsApp.14 Puntland visas for the Kenyan crewmembers were arranged through an Oman-based company named Somlink Fisheries Investment Co., headed by Abdulkadir. In a 22 April 2019 letter to Puntland immigration authorities, Abdulkadir provided names and passport details for the 13 Kenyan crewmembers. Puntland immigration officials subsequently approved the visas, and the Kenyan crewmembers travelled to Bosaso that same month and boarded the Marwan 1.

April 2019 letter from Somlink Fisheries Investment Co. director ‘Abdulkadir’ requesting Puntland visas for 13 Kenyan nationals intended to crew the Marwan 1.

According to members of this crew, the Marwan 1 turned out to be another forced labour fishing operation. From April to July 2019, the Kenyan crew endured deplorable working conditions, leading to multiple untreated injuries.15 They were reportedly forced to work up to 20 hours per day and sleep in the open, and were denied medical treatment.16 Following a confrontation with the captain of the vessel, crewmembers were denied food for two days and were threatened with being locked in cold storage and being shot.17 In July 2019, the crew eventually managed to contact the International Transport Workers’ Federation, which in turn notified the Kenyan ambassador to Somalia. The following month, the seafarers returned home to Kenya after a long and onerous repatriation journey.18 Despite being promised a salary of KES 26 000 (US$240) per month,19 each crewmember ultimately received between US$450 and US$500 for a total of four months’ work, which was only sufficient to purchase airfare back to Kenya.20

A representative of Somlink Fisheries disputed this account, stating that the company had been misled by the Kenyan recruiting agent and that the crew the agent had provided were unqualified, with some never having served on a fishing vessel before.21 According to the representative, Somlink discharged the crew with full compensation.22

The repatriation of its Kenyan crew did not immediately end the fishing operations of the Marwan 1 in Somalia. Nor did the fact that in December 2019, the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC), a 31-member intergovernmental organization responsible for the management of tuna and tuna-like species, publicly listed the Marwan 1 as an IUU fishing vessel.23 According to the IOTC, the Marwan 1 was observed fishing in Somali waters on 15 September 2020.24 Most recently, reporting suggests that the vessel was documented by international naval forces in Puntland waters in December 2020.25 The crew most likely comprised Indonesian, Somali and Yemeni nationals and was in possession of a purported Puntland fishing licence, the authenticity of which could not be verified.26

A representative of Somlink Fisheries claimed that the vessel had since ceased fishing operations. He stated that the blacklisting of the vessel by the IOTC had rendered fishing operations untenable and that the company therefore intended to convert the Marwan 1 into a supply vessel. The company claimed that the vessel had been ‘illegally’ blacklisted, as it did not fish tuna or tuna-like species and was therefore not subject to IOTC jurisdiction.27 It further claimed that the blacklisting had been politically motivated, stemming from the Somali federal government’s preference for issuing licences to Chinese-flagged tuna longliners at the expense of Puntland-based vessels.28

Al Wesam fishing, somlink fisheries and the identity of ‘Abdulkadir’

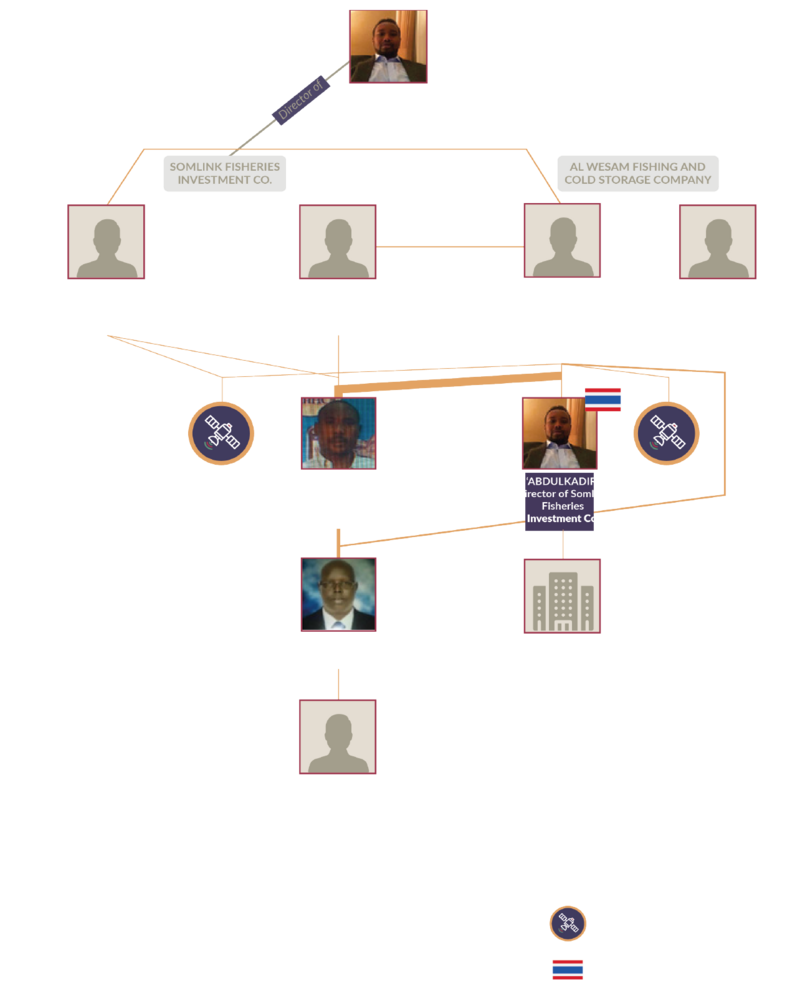

The GI-TOC has determined that Al Wesam Fishing and Cold Storage Company – the front company that operated the Al Wesam fleet – and Somlink Fisheries, the company responsible for recruiting the 13 Kenyan seafarers, are operated by the same family originating in Bosaso, Somalia. Subscriber data for four Somali mobile-phone numbers affiliated with the two companies showed the numbers to be registered to three brothers, each of whose names contained variant spellings of ‘Abdulkadir’. Moreover, one number affiliated to Al Wesam Fishing, and a second number affiliated to Somlink Fisheries, were both registered to the same individual, ‘Shermaarke Abdulqadir Mohamed’.

Contacts affiliated with Somlink Fisheries and Al Wesam Fishing, June 2016–November 2019

Note: Mobile-phone records were used to map communications by numbers affiliated with Somlink Fisheries and Al Wesam Fishing. The thickness of the lines connecting the individuals and entities is indicative of the relative frequency of communication.

Mobile-phone records obtained by the GI-TOC provided further evidence of ties between the two companies. For instance, the Thai mobile-phone number used by Somlink representative Abdulkadir to contact Seaport Operations Limited in Mombasa was in turn contacted twice by a phone number affiliated with Al Wesam Fishing in early 2019.29 Revealingly, analysis of call records for the Somali mobile-phone numbers affiliated with both Somlink Fisheries and Al Wesam Fishing show numerous contacts with known arms traffickers in both Somalia and Yemen previously identified by the GI-TOC as members of the ‘Mohamed Omar Salim network’ (Figure 6).30 The individuals contacted by Somlink and Al Wesam included the prominent Puntland-based arms trafficker Abdirahman Mohamed Omar (aka ‘Dhofaye’) and Yemen-based trafficker Mohamed Hussein Salad. These communications may constitute preliminary evidence of a nexus between IUU fishing and arms trafficking operations, the existence of which has been previously hypothesized by the GI-TOC.31

Following repeated inquiries, a representative of Somlink Fisheries acknowledged that the Abdulkadir family had previously partnered with the Sangsukiam family in Thailand, facilitating the latter’s fishing operations in Somalia.32 He identified their point of contact as Wichai Sangsukiam, the brother of former Thai senator and Sangsukiam family patriarch Wanchai Sangsukiam.33 Following the exposure of the Al Wesam fleet’s IUU fishing activities, the representative claimed that the family had purchased the Al Wesam 4 from its Thai owners and renamed it the Marwan 1.34 The vessel, he told the GI-TOC, was jointly owned by 20 family members; following the purchase, all business ties with the Sangsukiams were severed.35 The other three vessels formerly comprising the Al Wesam fleet, he further claimed, were sold by their Thai owners to Burmese or Cameroonian companies following the vessels’ blacklisting by the IOTC.36

IUU fishing in Somalia is often cast domestically in nationalistic terms, as a foreign predation on a weak and divided country. However, as the story of the Somali 7 shows, IUU fishing operations in Somali waters are, in reality, abetted by a network of local enablers, both inside and outside state institutions. Rampant corruption within Somali state institutions continues to foster a dynamic whereby foreign fishing actors can act with impunity. So long as this dynamic persists, it will contribute to the environmental destruction of Somalia’s marine resources and undermine the long-term ability of the state to generate legitimate revenue from fisheries.

This article is an extract from ‘Fishy business: Illegal fishing in Somalia and the capture of state institutions’ by Jay Bahadur, an upcoming report from the GI-TOC’s Observatory of Illicit Economies in East and southern Africa. The report presents a series of detailed case studies of IUU fishing practices in Somalia, each illustrating a different facet of corruption within Somali state institutions and documenting the criminality and corruption associated with the Somali fishing industry in detail.

Notes

-

See, for instance, One Earth Future, Somali perspectives on piracy and illegal fishing, 10 July 2016, https://www.oneearthfuture.org/research-analysis/somali-perspectives-piracy-and-illegal-fishing; Abdiqani Hassan, Somali regional anti-piracy chief says sacked over illegal fishing comments, Reuters, 21 March 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-somalia-piracy/somali-regional-anti-piracy-chief-says-sacked-over-illegal-fishing-comments-idUKKBN16S0LA?edition-redirect=uk; and Jason Patinkin, Somali fishermen struggle to compete with foreign vessels, VOA, 20 May 2018, https://www.voanews.com/africa/somali-fishermen-struggle-compete-foreign-vessels. ↩

-

Jay Bahadur, The Pirates of Somalia. London: Vintage Books, 2011. ↩

-

Ian Urbina, The Outlaw Ocean: Journeys Across the Last Untamed Frontier. New York: Knopf, 2019. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

For more information on the Sangsukiam family, see Turn the tide: Human rights abuses and illegal fishing in Thailand’s overseas fishing industry, Greenpeace, 16 December 2016, https://www.greenpeace.org/aotearoa/publication/turn-the-tide-human-rights-abuses-and-illegal-fishing-in-thailands-overseas-fishing-industry. ↩

-

Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS), internal report on IUU fishing in Somalia, April 2020. ↩

-

Indian Ocean Tuna Commission, IOTC circular 2018-36, 8 August 2018, https://www.iotc.org/sites/default/files/documents/2018/08/Circular_2018-36_-_Communication_from_Thailand_wrt_IUU_VesselsE.pdf. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Stop Illegal Fishing, Investigation No. 21: Misery on the MARWAN 1, 10 December 2020, https://stopillegalfishing.com/publications/investigation-no-21-misery-on-the-marwan-1/. ↩

-

Interview with the agent responsible for recruiting crewmembers for the Marwan 1, 4 February 2021, by phone. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Anthony Kitimo, Ordeal of Kenyans stuck on Somali fishing vessel, East African, 11 July 2019, https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/news/east-africa/ordeal-of-kenyans-stuck-on-somali-fishing-vessel-1422280. ↩

-

Stop Illegal Fishing, Investigation No. 21: Misery on the MARWAN 1, 10 December 2020, https://stopillegalfishing.com/publications/investigation-no-21-misery-on-the-marwan-1/. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Anthony Kitimo, Ordeal of Kenyans stuck on Somali fishing vessel, East African, 11 July 2019, https://www.theeastafrican.co.ke/tea/news/east-africa/ordeal-of-kenyans-stuck-on-somali-fishing-vessel-1422280 ↩

-

Stop Illegal Fishing, Investigation No. 21: Misery on the MARWAN 1, 10 December 2020, https://stopillegalfishing.com/publications/investigation-no-21-misery-on-the-marwan-1/. ↩

-

Interview with a representative of Somlink Fisheries Investment Co., 10 March 2021, by phone. ↩

-

Interview with a representative of Somlink Fisheries Investment Co., 5 March 2021, by text message. ↩

-

Indian Ocean Tuna Commission, IOTC Circular 2019-54, 11 December 2019, https://www.iotc.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019/12/Circular_2019-54_-_Request_to_update_the_IUU_Vessels_list.pdf. ↩

-

Indian Ocean Tuna Commission, IOTC Circular 2020-47, 30 October 2020, https://www.iotc.org/sites/default/files/documents/2020/10/Circular_2020-47-_A_communication_from_THA_on_the_IUU_vessel_MARWANE.pdf. ↩

-

Interview with a confidential maritime source, 4 February 2021, by phone. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Email from the director of Somlink Fisheries Investment Co., 29 May 2021. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Mobile-phone records on file with the GI-TOC. ↩

-

Jay Bahadur, Snapping back against Iran: The case of the Al Bari 2 and the UN arms embargo, GI-TOC, November 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/analysis/iran-pb/. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with a representative of Somlink Fisheries Investment Co., 10 March 2021, by phone. ↩

-

Ibid. For more information on Wichai Sangsukiam, see Turn the tide: Human rights abuses and illegal fishing in Thailand’s overseas fishing industry, Greenpeace, 16 December 2016, https://www.greenpeace.org/aotearoa/publication/turn-the-tide-human-rights-abuses-and-illegal-fishing-in-thailands-overseas-fishing-industry/. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

Interview with a representative of Somlink Fisheries Investment Co., 23 February 2021, by text message. ↩