The life of a Kenyan charcoal transporter: a crucial role in a vast, vital and criminalized market.

James, 50, is a matatu (minibus taxi) driver in Embakasi, in the south-east of Nairobi. His name has been changed here. In addition to ferrying residents around the city, he also regularly travels to Meto, a district far to the south that is close to the border with Tanzania, in order to transport charcoal produced in the district back to the capital.1 As mundane as this journey may seem, thanks to a ban imposed on charcoal production and trade in Kenya, James is in fact transporting contraband goods.

High demand for charcoal means that a ‘grey market’ for charcoal continues in Kenya, facilitated by criminality and corruption. A GI-TOC research team has been conducting a study investigating the role of organized crime in the charcoal trade in Kenya, Uganda and South Sudan. James’s role, as a charcoal transporter bringing illicit fuel to the capital, illustrates what we have found to be the key elements of criminality in this vast, vital and often outlawed market.

Regulating the charcoal trade

Charcoal is an essential energy source in East Africa: it is cheap, efficient and easily transportable. In rapidly urbanizing areas, alternative energy sources are often simply not affordable or available.2 The charcoal market is also a key source of employment: in Kenya, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry estimated in 2016 that the charcoal trade was the largest informal-sector employer, employing 700 000 people, who in turn were believed to be supporting between 2.3 million and 2.5 million dependants.3

Yet demand for charcoal has led to widespread de-forestation and damage to ecosystems and biodiversity that, in turn, threatens the environment that sustains rural populations.4 Regulation of the charcoal market demands a difficult balancing act: the quality of life of millions of urban residents and employment in poor communities on the one hand, and the need to preserve biodiversity and reduce carbon emissions on the other.

Yet some governments in East Africa have turned to blunt instruments in order to achieve this fine balance. In Kenya, this came in the form of the nationwide moratorium on charcoal production and trade in domestically produced charcoal – although the commodity can still be legally imported –, first introduced in 2018 and still in effect today.5

A charcoal trader packs charcoal in small tins for sale in Nairobi in 2019. The charcoal market in Nairobi can be described as a ‘grey market’, as legally imported charcoal is sold along with – and indistinguishable from – charcoal that has been illicitly produced.

Photo: Simon Maina/AFP via Getty Images

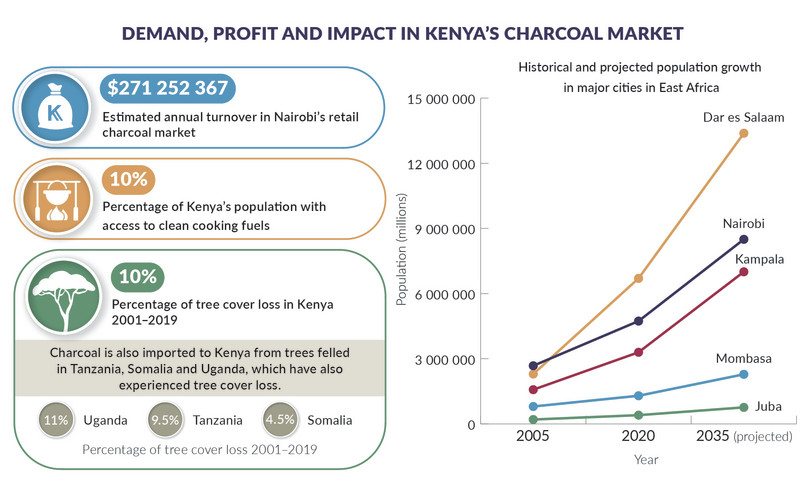

Note: Despite the national moratorium on charcoal production, the charcoal market in Nairobi continues to turn a significant annual profit, worth millions of dollars. Most of Kenya’s population do not have access to clean cooking fuels and instead rely on fuels such as charcoal for their daily needs. Rapid urbanization across East Africa is contributing to rising demand for energy. The incentive to produce charcoal – by illicit as well as legal means – is therefore set to increase in the future.

Source: Global Forest Watch; The Energy Progress Report; Population Stat.

The aim of this moratorium is to conserve the country’s forests. However, our research has found that it has had unintended consequences. According to charcoal producers, the moratorium damaged the livelihoods of those in producing areas. ‘The ban came like death; there was no forewarning,’ says Tsingwa Nduria, chairperson of the 2 000-member charcoal producers association in Msambweni, on Kenya’s south-east coast.6

Despite the disruption, the trade has continued as a lucrative grey market, where corruption and criminality now exist along the value chain. Other studies on the effects of trade bans on other commodities where demand is not elastic have made similar findings.7 As banning charcoal does not reduce demand in itself, those in the market will continue to operate illegally if the potential benefits outweigh perceived risks of legal sanctions.

Charcoal by minibus

James, the charcoal transporter, begins his journey from Nairobi at 7pm to reach Meto by midnight. The charcoal sale is arranged between James’s boss, a charcoal dealer, and a broker working in the Meto forest region. The broker ensures enough charcoal is collected from ‘bases’ of charcoal production throughout the forest to meet his dealer’s needs.

At the production level, the very act of harvesting wood for charcoal production is illegal, but production has nevertheless persisted. In some regions of Kenya, such as Kitui and Kajiado, local communities are sometimes intimidated into producing charcoal for dealers who control the region’s market.8 In Kajiado, a cartel involving local chiefs, Kenya Forestry Service officers, police and some politicians has reportedly targeted private and communal land that is home to indigenous tree species for charcoal production.9

A highway cuts through the town of Ilbisil, a key trafficking centre for charcoal produced in Kajiado County. Kajiado is allegedly home to a cartel that controls charcoal production involving local chiefs, Kenya Forestry Service officers, police and some politicians.

At sunset the following day, James begins his return journey. The transportation of charcoal involves attempting to evade law enforcement or negotiating a series of bribes along the route. James’s boss, the dealer, uses matatu drivers like James for transportation, both because of their speed and because of their know-how in dealing with police. How much a transporter pays per bribe varies, but they are able to estimate what they are likely to pay based on the quantity of their charcoal consignment.

Due to the higher risk of transporting charcoal under the ban, transporters, or dealers who control transport, push up prices to account for money paid as bribes or potential losses due to confiscation and arrests. A charcoal dealer in Nairobi said that the increased risk of having trucks seized by the police, or of arrest, has forced transporters who are not ‘protected’ by dealers out of business.10

James first drives his truck to a car wash at Ilbisil, where all the dust and mud is removed, to avoid detection by traffic police on the lookout for charcoal. Dusty vehicles believed to come from forests draw attention. He then sets out for Nairobi.

He pays KSh3 000 (US$27.70) at the first police roadblock. This is a standard bribe that has remained consistent for some time. The second roadblock is at the weighbridge at Mlolongo – about 20 kilometres from Nairobi’s central business district. Here, he pays KSh5 000 (US$46.13). This roadblock draws police and the county council inspectorate officers, and one must take care of them all. At any other roadblocks in between, he pays an average of KSh1 000 (US$9.20). If James is unlucky, he will cross paths with a patrol car from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations. His misfortune would cost him KSh10 000 (US$92.25).

Aside from bribes made to police along the route, James also makes payments to owners of farms passed when moving charcoal from the forest to the main highway, in order to ensure their cooperation.11 Informal agreements may also be formed between charcoal transporters and the police. These include what is known as kusafisha barabara, meaning ‘to cleanse the road’ in Kiswahili. A dealer who sources charcoal from Busia, Ilbisil and Kajiado described how this entails collusion between powerful charcoal dealers and the police service, whereby police are withdrawn from major transport routes, allowing the unimpeded flow of charcoal from point to point.12 If roadblocks and patrols need to be reintroduced, dealers will receive prior notice from the police involved.

According to Luka Chepelion, a member of the County Executive Committee in charge of Environment and Forestry in West Pokot, north-west Kenya, police have also been reported actively transporting charcoal themselves.13 In at least one instance, a large load was confiscated only to reportedly disappear from the inventory, likely sold to another dealer.14

Indeed, since the moratorium, charcoal has come to provide a major source of income for corrupt police officers, who actively seek out opportunities to ‘tax’ the illicit trade. For example, between Lunga Lunga and Likoni – a 95-kilometre route often used by charcoal transporters – there are about 19 roadblocks in an area that is supposed to have just one.15

James arrives in Nairobi between 3am and 4am, just before people pour out onto the streets. His final task as a driver is to evade the city’s traffic police, before delivering his consignment to its final destination. Due to the costs of bringing the charcoal to market, prices for the fuel have increased since the moratorium was imposed.

Despite the intentions of the charcoal moratorium, ever-increasing demand for cheap energy in urban centres and the ability of dealers and transporters to consistently evade and collude with law enforcement means that the charcoal market is still a lucrative proposition in Kenya. In James’s words, ‘after doing this for years, I have come to accept that charcoal is gold’.

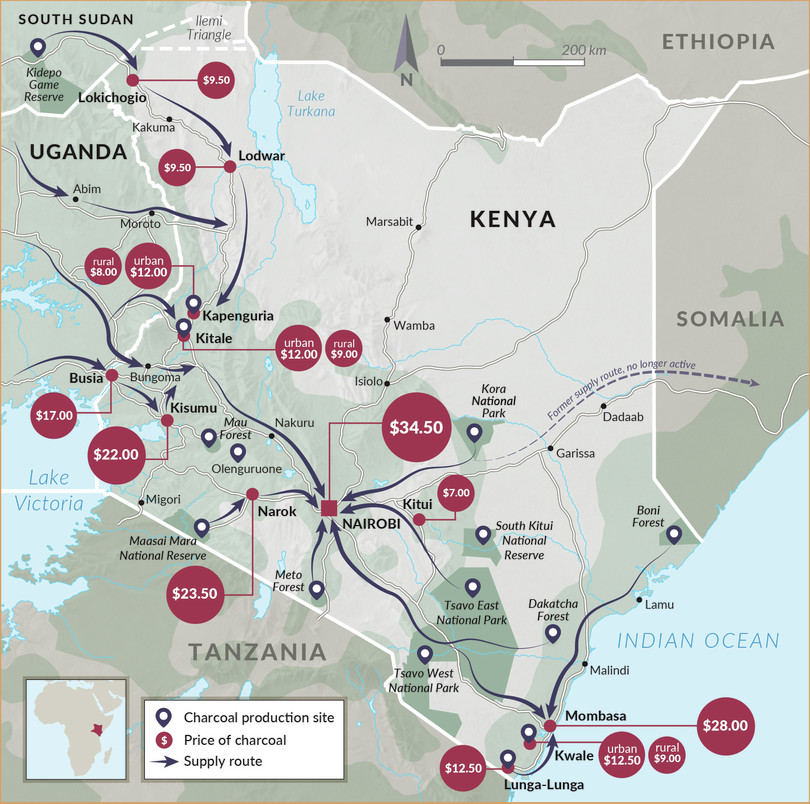

Figure 4 Transport routes for charcoal and retail charcoal prices in Kenya.

Note: Price data collected from GI-TOC fieldwork looking at criminality in the charcoal market in East Africa.

Notes

-

Interview in Eastlands, Nairobi, 24 July 2020. ↩

-

See Adam Branch and Giuliano Martiniello, Charcoal power: The political violence of non-fossil fuel in Uganda, Geoforum, 97, 2018, 242–252, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.012; Gerald Shively et al., Profits and margins along Uganda’s charcoal value chain, International Forestry Review, 12, 3, 2010, 270–283, https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/articles/ajagger1001.pdf. ↩

-

Kenyan Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, National Forest Programme of Kenya 2016–2030, 2016, http://extwprlegs1.fao.org/docs/pdf/ken190060.pdf. ↩

-

Julie A Silva et al., Charcoal-related forest degradation dynamics in dry African woodlands: Evidence from Mozambique, Applied Geography, 107, 2019, 72–81, https://doi.org/10.1016/J.APGEOG.2019.04.006; Marianne Mosberg and Siri H Eriksen, Responding to climate variability and change in Dryland Kenya: The role of illicit coping strategies in the politics of adaptation, Global Environmental Change, 35, 2015, 545–557, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.09.006; Gerald Shively et al., Profits and margins along Uganda’s charcoal value chain, International Forestry Review, 12, 3, 2010, 270–283, https://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/articles/ajagger1001.pdf. ↩

-

Kenyan Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources, Press Statement: Extension of the Moratorium on Logging Activities in Public and Community Forests, 16 November 2018, http://www.environment.go.ke/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/4048264.pdf. ↩

-

Interview with Tsingwa Nduria, Lunga Lunga, 3 September 2020. ↩

-

Criminological literature has largely been wary of trade bans as an effective measure for controlling markets for goods for which demand is inelastic. See for example Kirsten Conrad, Trade bans: A perfect storm for poaching? Tropical Conservation Science, September 2012, doi: 10.1177/194008291200500302. ↩

-

This was reported in separate interviews with multiple sources, including dealers, transporters, brokers and police; July-August 2020, in Kajiado and Kitui. ↩

-

This allegation was made by several interviewees, Interview with Kajiado-based newspaper reporter who has extensively covered charcoal activities in the County, Kitengela Town, 4 August 2020. Interview with Charles Wambugu, Kajiado Central sub county commissioner in Kajiado Town, 13 August 2020. Ministry of Environment and Forestry, Taskforce Report in Forest Resources Management and Logging Activities in Kenya, April 2018. ↩

-

Interview with Mwalimu, a charcoal dealer, Nairobi, 9 August 2020. ↩

-

James reported this ‘toll fee’ to each farm as being a small payment of KSh200 per vehicle passing through. Mostly charcoal from Meto passes through five farms before getting onto the Namanga Highway on its destination. ↩

-

Interview with a dealer who sources charcoal in Busia, Ilbissil and Kajiado, 9 August 2020. ↩

-

Interview with Luka Chepelion, West Pokot County CEC in charge of Environment and Forestry, Kapenguria Town, September 2020. ↩

-

Interview with a Kajiado-based newspaper reporter who has extensively covered charcoal activities in the county, Kitengela Town, August 2020. ↩

-

This was reported in several interviews in the region, including with dealers, officials of charcoal producing associations (CPAs), police and county government personnel, between 1 and 4 September 2020. This was also observed during GI-TOC fieldwork in Kwale in September 2020. ↩