The prosecution and subsequent acquittal of an Iranian crew accused of trafficking heroin by dhow in the Seychelles highlights trends in drug trafficking in the Indian Ocean basin

In April 2016, a vessel of the Seychelles Coast Guard intercepted an Iranian-flagged dhow – a small fishing vessel – named the Payam Al Mansur, which was found to be carrying almost 100 kilograms of heroin and almost 1 kilogram of opium. The ensuing prosecution and subsequent acquittal on appeal of two crew members has been one of the most high-profile drug-trafficking cases prosecuted in the Seychelles in at least the past five years.1 The case appeared emblematic of the unique role dhows seem to play in the trafficking of illegal goods – including but not limited to drugs – in the Indian Ocean and along the East African coast.

The curious case of the Payam Al Mansur

The two individuals brought to trial in the Payam Al Mansur case were Emam Bakhsh Tarani, the captain, and Hattam Mothashimina, the son of the owner of the vessel. Charges against a third member of the crew, an engineer, were withdrawn before the start of the trial due to a lack of evidence that he was aware of the illicit cargo on board.

Testifying in late 2017, both men described how the vessel had departed its home port of Konarak, Iran, purportedly on a fishing trip to Tanzania. Both denied any knowledge of the drugs and alleged in their testimony that the vessel’s owner, Mothashimina’s father, had placed the drugs on board the ship before the crew had set out on their voyage.2 In the face of the forensic analysis of the drugs and the testimony of the Seychelles Coast Guard and police officers who participated in the seizure, both Tarani and Mothashimina were convicted on drug-trafficking charges in early 2018 and given life sentences.3

However, the judgment of an appeal delivered in mid-December 2018 complicated what had initially seemed to be a straightforward prosecution.4 The appeal found that the trial judge had been in error in finding that the prosecution had proven beyond doubt that the ship had been seized in Seychellois territorial waters. While coastguard officials had testified that the vessel had been intercepted four nautical miles from Bird Island (a small island in the northernmost area of the Seychelles archipelago), no corroborating documentation (such as the ship’s logbook) was produced by the prosecution. Footage of the interception in action likewise did not establish precisely the location of the action recorded. The appeal duly overturned the convictions of Tarani and Mothashimina on the grounds that the offence was not proven to have been committed in the territorial waters of the Seychelles, not on any evidential issue over whether the ship and the convicted crew members were involved in drug trafficking.

There is also an ongoing legal battle over custody of the dhow itself, which in the years since its seizure has been used by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) as a training vessel for law-enforcement officers.5 The dhow’s owner, Malik, appealed to the courts in March 2019 for its release, but the Seychelles authorities argue that it is still subject to forfeiture as the proceeds of crime.

Dhow trade, both legal and illegal

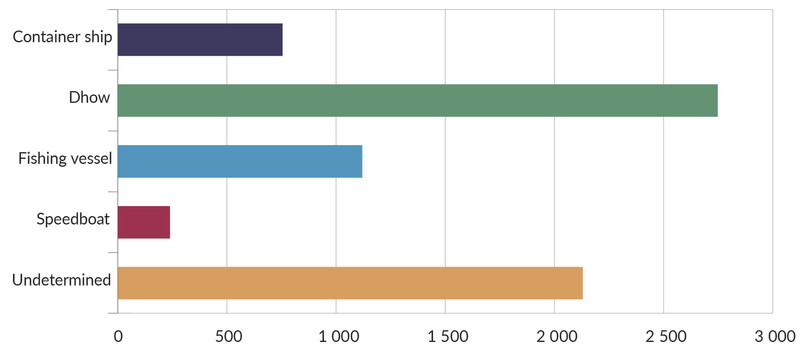

Seizure data shows that dhows, and in particular Iranian dhows such as the Payam Al Mansur, are the primary means by which heroin is trafficked from the Makran coast of Iran and Pakistan throughout Indian Ocean coastal states and islands. Analysis of reported seizures of heroin in the Indian Ocean region shows that a greater volume of heroin was seized from dhows in 2019 than any other vessel type.

But dhow-based trafficking of illicit goods is by no means limited to heroin. Interceptions of dhows made by international maritime forces such as the Combined Task Force 150 (CTF 150) – an international naval force tasked with countering piracy, terrorism and trafficking off the Horn of Africa – have detected dhows carrying shipments of weapons from Iran to Somalia and Yemen, as well as large cargos of methamphetamines, hashish and cannabis to destinations around the Horn of Africa.6 Recent GI-TOC research on trafficking routes between Zanzibar, northern Mozambique and the Comoros has tracked human-smuggling operations using dhows along the East African coast – the so-called ‘southern route’ by which migrants travel from the Horn of Africa, largely towards South Africa.7 According to Per Erik Bergh, director of the NGO Stop Illegal Fishing, investigations conducted by Stop Illegal Fishing and Greenpeace to counter illegal fishing off the coast of Tanzania also found large-scale smuggling of charcoal taking place in dhows travelling between Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania and Zanzibar, as well as the aforementioned human-smuggling routes.8 Charcoal from Somalia is under UN Security Council sanction and the charcoal trade has been established as source of funding for Al-Shabaab.

In part, the ubiquity of dhows in seaborne trafficking in the Indian Ocean reflects the widespread use of these vessels in legal trade and fishing. For hundreds of years, small wooden dhows plied the trade routes between East Africa, the Gulf states and India, and they continue to occupy a vital niche in the regional maritime economy today, having evolved to become larger, engine-powered vessels capable of managing long voyages. The Payam Al Mansur – a Jelbut-type engine-powered dhow which can be up to 50 feet in length – is typical of the type of dhow produced in Iran and used widely in the Indian Ocean today, both in fishing and the transport of cargo.9

Modern dhows carry a range of commodities, from steel and coal to grain and livestock, between India, the Gulf countries and East Africa.10 For years, dhows based in the UAE have helped Iran circumvent trade sanctions, with dhows carrying everyday consumer goods from the UAE to Iran via the re-export trade.11 And while some dhows may have been intercepted carrying illegal shipments of weapons to Yemen, others have provided vital humanitarian supplies to the war-torn country, which larger-scale sea cargoes are unable to reach.12

Figure 4 Volume of heroin seized from different vessel types in the Indian Ocean, January–December 2019 (kilograms)

NOTE: ‘Undetermined’ consists of two seizures: two tonnes of heroin with 99 kilograms of crystal methamphetamine seized by Egyptian security forces, April 2019; and 130 kilograms of heroin seized by the Pakistan Maritime Security Agency, September 2019. No public information is available specifying the type of vessel involved.

According to some ethnographers, dhows continue to be used in the Indian Ocean thanks to their ability to travel where commercial, large-scale shipping cannot, whether due to security issues or the limited capacity of some ports.13 According to Bergh, the ports used by dhow crews are often separate from main shipping container ports and, historically, not subject to the same regulatory scrutiny.14 These factors, coupled with the fact that dhow-based trade is often informal and unregulated, has historically allowed illegal commodities to be easily concealed within other cargoes.15

However, this picture is reportedly changing. According to Alan Cole of the UNODC Global Maritime Crime Programme, recent months have seen a shift away from dhow-based trafficking towards other types of vessels. Other experts interviewed in the course of Global Initiative research have suggested that bulk carriers (larger merchant ships designed to transport unpackaged large cargoes) are becoming more commonly used.16 According to Cole, the reputation that seagoing dhows have acquired for being involved in trafficking, along with improved methods of identifying dhows involved in criminal activity (for example, by their behaviours and methods of loading), have made it more difficult for dhow crews to operate under the radar of the authorities.17

Shifting routes through the Indian Ocean

The acquitted crew members of the Payam Al Mansur maintained that Tanzania, rather than the Seychelles, was their ultimate destination. If true, this is in keeping with maritime routes to Indian Ocean island states such as the Seychelles, which are reported to predominantly pass via the East African coastline, including Tanzania and Kenya.18 Although dhows from the Iranian coast do travel to the Seychelles directly (reportedly dropping cargoes of heroin offshore to smaller fishing vessels from the Seychelles) before heading to East Africa, 19 the more circuitous route – heading to the mainland first, then back east to the islands – is reported to be more frequently used by trafficking networks.

A boarding party from the Australian naval vessel HMAS Melbourne – operating as part of the Combined Task Force 150 – intercept a dhow found to be carrying nearly 2 tonnes of cannabis resin. As can be seen from the logo on the hull of the vessel, this dhow was manufactured by the Al Mansoor company.

SOURCE: Australian Government, Department of Defence

The Payam Al Mansur docked in the Seychelles after it was intercepted carrying almost 100 kilograms of heroin and almost 1 kilogram of opium by Seychelles authorities in April 2016.

SOURCE: UNODC Maritime Crime Programme, via Twitter

However, more rigorous law enforcement in Tanzania has apparently spurred trafficking networks to adopt different routes,20 travelling south towards Mozambique21 or, increasingly, arranging trans-shipment via eastern Indian Ocean states such as Sri Lanka.22 Sri Lankan and Seychellois law-enforcement agencies were reportedly coordinating investigations in 201923 after the seizure of over 200 kilograms of heroin in a Sri Lankan port in December 2018 revealed a trafficking network which had reportedly been repeatedly shipping heroin to the Seychelles by sea.24

Al Mansoor – a common thread in many trafficking cases

The facts of the Payam Al Mansur case resemble other dhow-based trafficking operations in some of the details. The dhow was manufactured by a Chabahar-based company named Al Mansoor.

Over the past decade, Al Mansoor dhows have featured in multiple trafficking cases. Analysis of open-source information on dhows seized in the Indian Ocean for this bulletin found 16 separate trafficking incidents involving Al Mansoor dhows, including the trafficking of heroin, methamphetamines and cannabis as well as weapons destined for Somalia and Yemen. The Payam Al Mansur dhow itself was seized in 2010 off Mozambique for illegal fishing offences,25 and, according to a senior UN official, has been reportedly been identified as being involved in other criminal activity by organizations tracking illicit flows across the Indian Ocean.26

Al Mansoor build dhows that may attract the interest of trafficking networks because the company is known to customize dhows according to the buyers’ needs, for example, by fitting custom compartments and large fuel tanks for the long journey to East Africa. Researchers have questioned whether the company has any knowledge of the manner in which their products may end up being used in illicit operations, but, despite repeated investigation into the company, there is no demonstrable link between Al Mansoor or any criminal enterprise. A 2016 report by Conflict Armament Research alleged that weapons shipments detected in Al Mansoor dhows could ‘plausibly derive from Iranian stockpiles’ of state weapons, and pointed out that the company headquarters in Chabahar is adjacent to an Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps facility. However, no such connection between the Revolutionary Guard Corps and Al Mansoor has been established. Nonetheless, Al Mansoor dhows seem to be a common logistical thread running between many smuggling businesses.

According to Cole, it is however sometimes possible to connect the companies that own and finance dhows travelling in the Indian Ocean with intent to traffic illegal goods.27

An opportunity missed

While in many ways the Payam Al Mansur case resembled many cases of heroin trafficking in the Indian Ocean – in terms of the vessel involved, the route travelled and even its manufacturer – it stood out as a rare opportunity for a major case of international maritime drug trafficking to be prosecuted in the island nation. Whereas seizures made in international waters by forces such as CTF 150 are not able to be prosecuted as they do not fall under the jurisdiction of one nation (the drugs seized are merely destroyed), this case offered the chance to gain much-needed insight into members of a trafficking network. However, the failure of the prosecution to establish the jurisdiction in which the crime was committed proved to be the stumbling block of the entire investigation, highlighting once again the challenges facing law enforcement in combating drug trafficking in the maritime domain.

Notes

-

A search of criminal cases prosecuted in the Seychelles in the past five years available through the online portal of the Seychelles Legal Information Institute (https://seylii.org)) does not present any comparable large-scale trafficking cases prosecuted in the past five years. ↩

-

Interview with Hattam Mothashimina in Seychelles detention, 1 June 2016, shared with author. Findings of the trial can be found here: R v Tarani & Anor (CO 25/2016) [2018] SCSC 45 (23 January 2018), Seychelles Legal Information Institute, https://seylii.org/sc/judgment/supreme-court/2018/45-0 ↩

-

R v Tarani & Anor (CO 25/2016) [2018] SCSC 62 (26 January 2018), Seychelles Legal Information Institute, https://seylii.org/sc/judgment/supreme-court/2018/62-0. ↩

-

Monthushimira & Anor v R (SCA CR 06 & 07/2018) [2018] SCCA 36 (14 December 2018), Seychelles Legal Information Institute, https://seylii.org/sc/judgment/court-appeal/2018/36-0. ↩

-

Interview with Alan Cole, UNODC Global Maritime Crime Programme, 20 May 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime research conducted for this bulletin has compiled instances of dhows found to be trafficking in illegal goods, both by CTF 150 and other forces. ↩

-

Alastair Nelson, A triangle of vulnerability: Changing patterns of illicit trafficking off the Swahili coast, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, forthcoming. See also Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, Risk Bulletin of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa, Issue 7, April–May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/GI-Risk-Bulletin-007-04May1845-proof-5.pdf. ↩

-

Interview with Per Erik Bergh, director of Stop Illegal Fishing, 19 May 2020, by phone. ↩

-

NATO Shipping Centre, Identification guide for Dhows, Skiffs and Whalers in the High Risk Area, https://www.norclub.com/assets/ArticleFiles/NATO-Guidance-for-ID.pdf. ↩

-

Vijay Sakhuja, Dhow Trade In The North Arabian Sea – Analysis, Eurasia Review, 8 August 2017, https://www.eurasiareview.com/08082017-dhow-trade-in-the-north-arabian-sea-analysis/. ↩

-

John Dennehy, Dubai’s historic dhow trade to Iran feels pressure from US sanctions, The National, 13 July 2019, https://www.thenational.ae/uae/government/dubai-s-historic-dhow-trade-to-iran-feels-pressure-from-us-sanctions-1.885424; Ben Thompson, Iran trade sanctions hit Dubai port, BBC World, 29 July 2010, https://www.bbc.com/news/business-10779331. ↩

-

Vijay Sakhuja, Dhow Trade In The North Arabian Sea – Analysis, Eurasia Review, 8 August 2017, https://www.eurasiareview.com/08082017-dhow-trade-in-the-north-arabian-sea-analysis/; World Food Programme Logistics Cluster, Yemen Humanitarian Imports Overview, August 2018, https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/logistics_cluster_yemen_humanitarian_imports_overview_180917.pdf. ↩

-

Jatin Dua, Captured at Sea: Piracy and Protection in the Indian Ocean. University of California Press, 2019. ↩

-

Interview, Per Erik Bergh, director of Stop Illegal Fishing, 19 May 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Interview, Per Erik Bergh, director of Stop Illegal Fishing, 19 May 2020, by phone. See also Lynsey Chutel, Heroin may be Mozambique’s second largest export—and it’s being disrupted by WhatsApp, Quartz Africa, 5 July 2018, https://qz.com/africa/1321566/mozambiques-heroin-drug-trade-disrupted-by-whatsapp-telegram/. ↩

-

Interview with Tom Carter, team leader of EU Action Against Drugs and Organised Crime (EU-ACT) programme, March 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Interview with Alan Cole, UNODC Global Maritime Crime Programme, 20 May 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Southern Route Partnership, Drug Trafficking on Maritime Routes to Island States of the Indian Ocean, conference paper, UNODC and Indian Ocean Forum on Maritime Crime, April 2018. ↩

-

Interview with Alan Cole, UNODC Global Maritime Crime Programme, 20 May 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Interview with Tom Carter, team leader of EU Action Against Drugs and Organised Crime (EU-ACT) programme, March 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Alastair Nelson, A triangle of vulnerability: Changing patterns of illicit trafficking off the Swahili coast, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, forthcoming. See also Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, Risk Bulletin of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa, Issue 7, April–May 2020, https://globalinitiative.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/GI-Risk-Bulletin-007-04May1845-proof-5.pdf. ↩

-

Interview with Alan Cole, UNODC Global Maritime Crime Programme, 20 May 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Sharon Ernesta, Sri Lanka police in Seychelles to investigate drug trafficking, Seychelles News Agency, 1 March 2019, http://www.seychellesnewsagency.com/articles/10581/Sri+Lanka+police+in+Seychelles+to+investigate+drug+trafficking. ↩

-

Colombo Page, Sri Lanka Police arrest a main suspect of 231-kg heroin haul, 7 December 2018, http://www.colombopage.com/archive_18B/Dec07_1544199269CH.php. ↩

-

Stop Illegal Fishing, Mozambique arrests an Iranian-flagged fishing vessel for IUU fishing, 12 May 2010, https://stopillegalfishing.com/news-articles/mozambique-arrests-an-iranian-flagged-fishing-vessel-for-iuu-fishing-5/. ↩

-

Interview with Alan Cole, UNODC Global Maritime Crime Programme, 20 May 2020, by phone. ↩

-

Interview with Alan Cole, UNODC Global Maritime Crime Programme, 20 May 2020, by phone. ↩