Groundbreaking new study of East and Southern African heroin markets out in April

In April, the Global initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime will release a unique study of heroin pricing, distribution and market dynamics in East and Southern Africa. The first of its kind, the study is intended to address significant knowledge gaps that hinder policy responses to the alarming growth in heroin trade in the region.

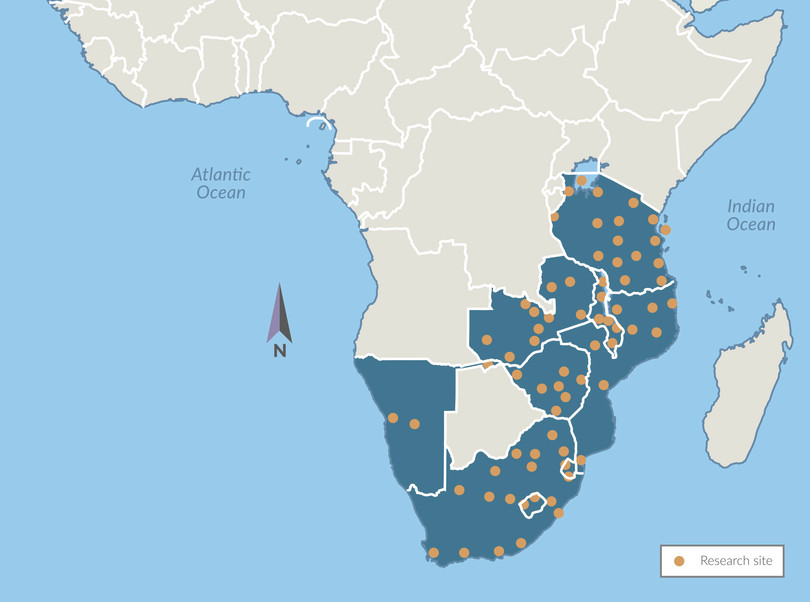

Over the past eight months we have scoured heroin markets in South Africa, Lesotho, eSwatini, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Zambia, Malawi and Tanzania for retail price data. We gathered price and marketplace data points on 113 heroin samples and interviewed 393 informants from 63 market sites across the nine countries of research. Interview subjects included people who use heroin; street and mid-level heroin dealers and distributors; heroin importers; law enforcement personnel; and, various levels of government officials.

Illegal drug prices provide a vital window into the variability and stability levels of a particular illegal drug market,1 make it possible to identify marketplace and flow linkages,2 and can be important metrics in the examination and understanding of drug-related policy and action.3

The report – A shallow flood: the diffusion of heroin in Eastern and Southern Africa – will contribute to a better understanding of drug markets through the lens of drug-pricing and -distribution systems, examine the mobility of drugs across and within markets and countries, and assess the responsiveness of markets and distribution systems to domestic law-enforcement efforts to disrupt or eliminate them.

Figure 6 Southern and eastern African regional sites where data on heroin prices and quality was gathered

Until now, there have been few attempts to analyze the embedded structural and contextual features of drug markets across the East and Southern African region, and particularly on the domestic characteristics of drug-pricing and -distribution systems within it and the efficacy of state efforts to restrict or disable these markets. This gap in knowledge has been highlighted in previous studies,4 and it is the intention of ongoing Global Initiative research to help address these gaps.

This research has revealed a significant diffusion of heroin supply and use across Eastern and Southern Africa and a proliferation of supply channels. Heroin has been ubiquitous across large swathes of Tanzania, Mozambique and South Africa for many years, but use is now proliferating in neighbouring Zambia, Lesotho and eSwatini and is emerging in rural areas across Zimbabwe.

Left: Smaller dealers are no less organized or industrialized than their larger-scale competitors. Most are entrepreneurial in their orientation and take an individualized approach to their business by pulling together bespoke orders for their volume-dealing clients. This heroin order was put together by a mid-level supplier in the Cape Town area, who sectioned the order by volume of ‘beats’. One beat retails for ZAR 80. There are 50 of these units in one plastic bank bag (known as a ‘banky’). The purchase price of this order for the client was ZAR 70 000. Several orders like this are filled by the supplier every day.\Right: A still taken from a video of a mid-level heroin supplier in Lesotho as she demonstrates the repackaging of kat heroin powder into 0.25g ‘handbags’ prior to putting together an order for distribution.

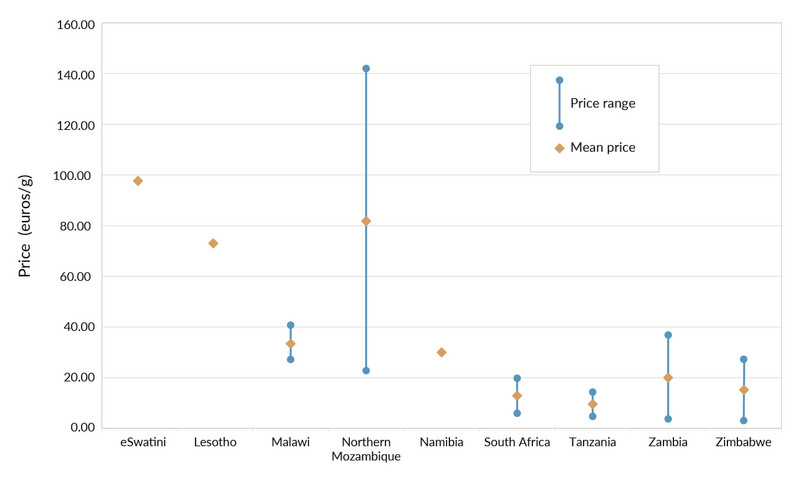

Figure 7 Heroin price ranges across the region

SOURCE: These are primary data collected as part of the First Round of regional illicit market price monitoring being led by the Global Initiative

A 0.25g packet of high-grade heroin available in Pemba, a core logistics and distribution point for heroin entering or transiting northern Mozambique. Selling for MT 2 500 a packet, the product is largely pure. Medium-quality versions sell for MT 750, and the lowest-quality for MT 400.

The relatively cheap retail heroin prices in South Africa and Tanzania suggest a high degree of product availability for distribution in domestic markets. The significant range in price for high-quality heroin in northern Mozambique suggests that the local market in that region consists primarily of high-volume heroin shipments landing in and transiting through the region, with small amounts of heroin from these shipments diverted into small local markets on an ad-hoc or payment-in-kind basis. The local availability of cheap, low-quality heroin in the same region, smuggled across the border from Tanzania to supply users in poor local mining communities, is additional evidence of the same pattern.

A 0.25g packet of ‘ngcono’ (good stuff) heroin sold in Mbabane, Matshapha, Manzini, Piggs Peak and Nhlangano, eSwatini. The cost is about €24.

Current continental drug-policy approaches, founded on prohibition, are not succeeding in disrupting or reducing heroin markets in Eastern and Southern Africa. In fact, these domestic markets continue to expand. Tough laws and mandatory minimum sentences are not stopping or reducing the distribution of illicit heroin or any other illegal substances. The continued unobstructed diffusion of heroin through the cities and towns of Eastern and Southern Africa should be seen as a natural consequence of prohibition-based approaches.5

Across the region, there are few fixed flows of heroin that can be identified and blocked using conventional, prohibition-style interdiction tactics. Rather than following distinct streams, the supply of heroin today is more akin to a shallow, slow-moving flood.

Because of the decades of impunity that traffickers have enjoyed, there are now multiple entry points into the region’s domestic markets, and many concurrent distribution channels established across the physical landscapes.

The region’s domestic heroin markets are now firmly, perhaps irrevocably, embedded. Heroin is distributed with various levels of purity, volume and regularity, and the markets are run by groups and networks of various sizes. Perhaps most worryingly, these markets are part of a stable, protected regional drug economy that stretches from Somalia to South Africa and is expanding inexorably into new, previously untapped markets in cities, towns and rural communities across the region.

Notes

-

J. Caulkins and P. Reuter, What price data tell us about drug markets, Journal of Drug Issues, 28, 3 (1998), 593–612; H. Brownstein and B. Taylor, Measuring the stability of illicit drug markets: Why does it matter? Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 90S (2007), S52–S60. ↩

-

S. Chandra and M. Barkell, What the price data tell us about heroin flows across Europe, International Journal of Comparative and Applied Criminal Justice, 37, 1 (2013), 1–13. ↩

-

J. Caulkins and P. Reuter, The meaning and utility of drug prices, Addiction, 91, 9 (1996), 1261–1264. ↩

-

Mark Shaw, Africa’s Changing Place in the Global Criminal Economy, Nairobi: ENACT, 2017; United Nations, The Afghan Opiate Trade and Africa: A Baseline Assessment, Vienna: UNODC, 2016. ↩

-

N. Magliocca, K. McSweeney, S. Sesnie, et al., Modeling cocaine traffickers and counterdrug interdiction forces as a complex adaptive system, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 116, 16 (2019): 7784–7792. The authors of this study described spatial and temporal responses by cocaine and heroin traffickers to interdiction efforts by the US Drug Enforcement Agency as a cat-and-mouse dynamic. ↩