Uganda’s Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act 2016 has left individuals vulnerable to abuse while failing to deter major drug traffickers.

In February 2016, after three years of lobbying and repeated attempts to pass the draft bill in Uganda’s parliament, the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (Control) Act came into force. The Act intensified Uganda’s already prohibitionist approach to drugs by significantly increasing penalties for all drug-related offences.

The Act has been controversial from the outset. Although lawyers in Uganda and law-enforcement officials praised the legislation, human-rights activists and rehabilitation centres criticized the harsh sentences it prescribed. The legislation also fails to properly distinguish between the offences of possession and trafficking, and places an overarching emphasis on a criminal-justice response to drugs rather than a public-health approach.1

Civil-society members argue that, while the Act has had a negligible impact on drug-trafficking networks, the most tangible change has been the level of abuse suffered by people who use drugs at the hands of law enforcement, and in the bribes they must pay to evade arrest.2 Law-enforcement officers highlight the dearth of alternatives to criminal-justice approaches, such as state-run rehabilitation clinics, in countering drug use.3

The Ugandan Human Rights Commission held a consultation on the Act in October 2019, in which a number of civil-society groups advocated the decriminalization of drug use.4 However, in Uganda’s current political climate, any reform is unlikely until after the 2021 national elections.

As part of its ongoing research into the political economy of illegal drug markets in Uganda, the Global Initiative has investigated how the technical practicalities of implementing the 2016 Act have had differing impacts on the rights of vulnerable people who use drugs and on organized-crime groups trafficking drugs.

Context

Following an established and familiar pattern across East and Southern Africa, Uganda has, over the past decade, become a significant transit country for Afghan heroin brought to the East African coast and destined for European markets. To a lesser extent, Uganda is also a transit state for South American cocaine destined for Europe. Rising rates of heroin consumption within Uganda also follow the patterns seen in countries across the region.5 Nominally, the 2016 Act was passed to counter these two trends.

High-level corruption connected to drug trafficking also provides a significant backdrop to implementation of the 2016 Act. The delays faced in passing the Act through parliament were attributed by interviewees to entrenched resistance among members of parliament, many of whom are believed to draw large profits from drug trafficking and therefore to have vested interests in blocking higher sanctions for traffickers.6 According to a US government submission in the 2019 drug-trafficking trial of the Kenyan brothers Baktash and Ibrahim Akasha, they and two associates attended a meeting at which Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni’s sister-in-law allegedly ‘offered to provide a license to import…ephedrine, two tons at a time, in exchange for a percentage of the profits’. The documents show that the Akasha network had ‘discussed using laboratories in Burundi, Uganda, and Tanzania to manufacture the ephedrine into methamphetamine’.7

Implementation of the Act

The 2016 Act adopts an approach common in African drug legislation, with escalating penalties for use, possession and trafficking. According to legal practitioners, the logic behind ascribing higher sanctions to possession than to use is that a person possessing narcotics could be seeking to deal in them.8 The higher penalty for possession applies even if the amount of drugs is small, although of course this can be taken into account during sentencing.

Although Uganda’s penalty structure is the same as, for example, Ghana’s, the impacts of the Ugandan legislation have reportedly been particularly punitive.9 While Ghanaian law-enforcement officers commonly charge those found in possession of a small quantity of illicit narcotics with use rather than possession, to enable a less punitive sentence,10 this trend has not been reported in Uganda.

Most cases of possession are tried in Uganda’s lower courts, which are not courts of record, so it is impossible to know the exact number of people arrested and charged under the Act. However, legal practitioners and law-enforcement officials reported that the vast majority of those arrested are charged with possession, and that the number of individuals charged with possession has significantly increased.11 Few trafficking cases are reported, and people who can afford a bribe are never charged.12

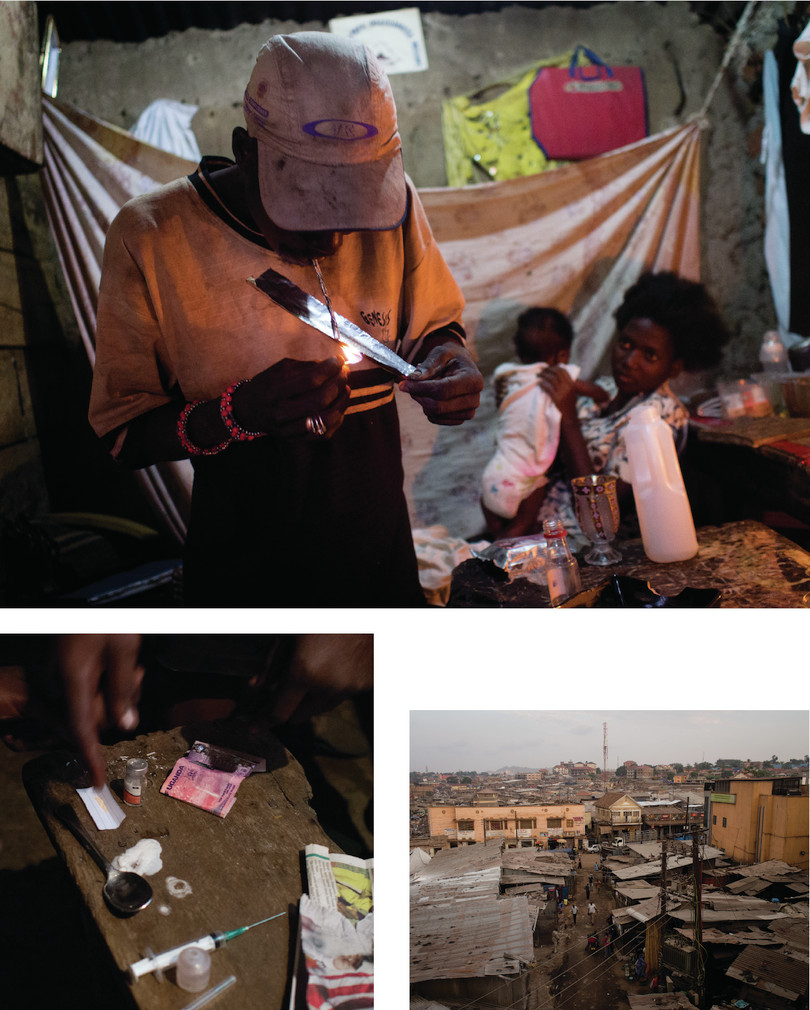

Four years after Uganda’s parliament passed a draconian anti-narcotics law, civil-society groups say the legislation has created an opportunity for corruption and persecution of people who use drugs. Here in Kisenyi, a slum in the heart of Kampala, photographer Michele Sibiloni captured a glimpse into the daily lives of addicts existing on the margins of society.

© Michele Sibiloni

For the trafficking cases that do come to trial, there are additional difficulties. The Act does not provide a clear distinction between the offences of possession and trafficking, such as a specific amount of narcotics. This is a crucial distinction, as sanctions for possession grant the judge discretion to sentence the perpetrator to a fine or imprisonment, or both, while those for trafficking mandate life imprisonment as well as a fine.

In spite of this mandate, trafficking penalties handed down by Ugandan courts since the Act came into force have been almost exclusively limited to fines.13 This is reportedly due to judicial fear of appeals against decisions.

The financial penalties imposed under the Act have been meaningless to higher-level drug traffickers but harshly punitive for disadvantaged people who use drugs. The Act dictates the same financial penalty for possession and trafficking: either a fine of not less than 10 million Ugandan shillings (€2 425),14 or ‘three times the market value of the narcotic drug … whichever is greater.’15 While the Act sets a minimum fine, in practice courts appear to have adopted the minimum as the standard amount.

As regards the market value of the drug, beyond stating that this should be documented in a certificate signed by an officer appointed by the minister responsible for internal affairs,16 the Act provides no guidance as to how the value is to be determined and, crucially, which market the price is based on. As of December 2019, no officer had been appointed, ‘market value’ remained undefinable and courts exclusively set fines based on the Act’s mandated minimum.

One 2019 lower court judgment reported to the Risk Bulletin confirms some of the trends identified, while calling others into question. A Venezuelan national arrested carrying 1.7 kg of cocaine and convicted on parallel counts of trafficking and possession, was reportedly sentenced to 11 years imprisonment on each count (22 years in total), together with the standard fine. While consistent with reports that the fines imposed are the minimum prescribed by the Act, it presents an exception to the reported lack of imprisonment for trafficking cases, although it still does not amount to the life sentence prescribed by the Act.17

One lawyer interviewed by the Global Initiative suggested that the intention of the Act is that the market value of seized narcotics is calculated based on the value at their intended destination, with the street price of drugs in New York or London used as a proxy. However, this presents significant challenges in accurately determining the drugs’ destination, and, in any case, an officer responsible for determining the price has not been designated.

Although the fines currently imposed are insignificant for large-scale traffickers, they outstrip what most drug users can afford. Failure to pay the fine is punishable by a 10-year prison term (a mandatory minimum sentence not subject to judicial discretion). The Act is noted to have fuelled extortion by law-enforcement officers, who give people who use drugs a choice between 10 years’ imprisonment and a bribe. Families and friends are often prevailed upon to provide funds to pay the bribe.18

Although imposing arguably disproportionate sanctions on people who use drugs, the current application of the Act’s sanctioning regime has made Uganda attractive as a transit country for drug-trafficking networks, for whom the relatively low penalties are merely a cost of doing business.19 In large part due to ineffective judicial implementation, and a lack of government guidance, the Act’s impact on large-scale drug-trafficking networks has been at best negligible and at worst counter-productive.

Notes

-

Uganda Harm Reduction Network, A press release on the condemnation of the human rights violations against people who use drugs by state operatives in Uganda, International Drug Policy Consortium, 23 January 2019, https://idpc.net/alerts/2019/01/uhrn-a-press-release-on-the-condemnation-of-the-human-rights-violations-against-people-who-use-drugs-by-state-operatives-in-uganda; Human Rights Awareness and Promotion Forum, The Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances (Control) Act, 2015 and the Legal Regulation of Drug Use in Uganda, October 2016, www.leahn.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Uganda-Analysing-report-2016.pdf. ↩

-

Interview with executive director of Ugandan civil-society organization providing support to people who use drugs (PWUD), Kampala, 19 December 2019. ↩

-

Interview with two senior officials, Anti-Narcotics Directorate of Criminal Investigations and Crime Intelligence (CID), Kampala, 16 December 2019. ↩

-

Interview with two senior officials, Anti-Narcotics Directorate of Criminal Investigations and Crime Intelligence (CID), Kampala, 16 December 2019, who also participated in the consultation. ↩

-

Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, Risk Bulletin of the Civil Society Observatory of Illicit Economies in Eastern and Southern Africa, Issue 2, November 2019, https://globalinitiative.net/esaobs-risk-bulletin-2/. ↩

-

Interviews with representatives of law enforcement and civil society, Kampala, December 2019. ↩

-

United States of America v Baktash Akasha Abdalla and Ibrahim Akasha Abdalla, United States District Court Southern District of New York, case 14 Cr. 716 (VM). ↩

-

Interview with senior law practitioner with experience in narcotics cases, Kampala, 17 December 2019. ↩

-

The Narcotic Drugs (Control, Enforcement and Sanctions) Law, 1990. ↩

-

Edward Burrows and Lucia Bird, Is drug policy in Africa on the cusp of change? The unfolding debate in Ghana, Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime, 12 September 2017, https://globalinitiative.net/is-drug-policy-in-africa-on-the-cusp-of-change-the-unfolding-debate-in-ghana/. ↩

-

Interview with two senior officials, Anti-Narcotics CID, Kampala, 16 December 2019; interview with senior police officer, Anti-Narcotics Desk, Central Police Station, Kampala, 16 December 2019; interview with executive director of Ugandan civil-society organization providing support to people who use drugs, Kampala, 19 December 2019. ↩

-

Interview with executive director of Ugandan civil-society organization providing support to people who use drugs, Kampala, 19 December 2019; interview with senior law practitioner with experience in narcotics cases, Kampala, 17 December 2019. ↩

-

Interview with two senior officials, Anti-Narcotics CID, Kampala, 16 December 2019; interview with senior law practitioner with experience in narcotics cases, Kampala, 17 December 2019. ↩

-

Article 4(1)(b)5, Narcotics Act 2016. ‘Currency point’ is defined in Schedule 1, Narcotics Act 2016. ↩

-

Article 4(1)(b)5, Narcotics Act 2016. ↩

-

Article 91, Narcotics Act 2016. ↩

-

Email exchange with senior law practitioner with experience in narcotics cases based in Kampala, 18 December 2019. ↩

-

Interview with executive director of Ugandan civil-society organization providing support to PWUD, Kampala, 19 December 2019. ↩

-

Interviews with representatives of Anti-Narcotics CID; conversation with representatives of international law-enforcement organization, November 2019, Brussels. ↩