Poor monitoring of South African citizens incarcerated abroad hampers consular services and crime-fighting efforts.

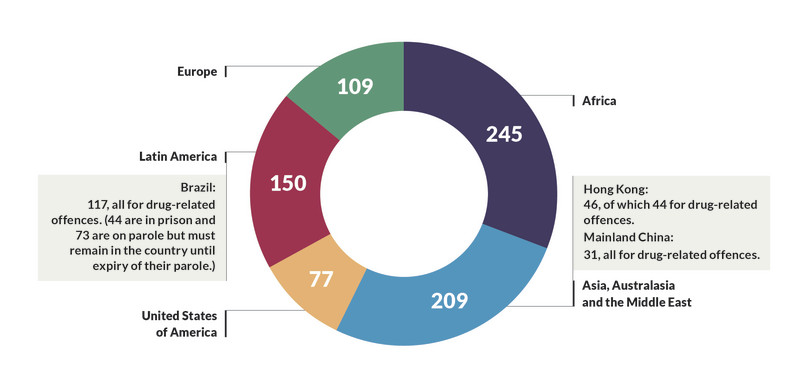

South Africa’s Department of International Relations and Cooperation (DIRCO) recently provided the GI-TOC with statistics for South Africans incarcerated abroad (see Figures 4 and 5). According to DIRCO, 71% of the 790 South Africans incarcerated abroad are serving sentences for drug-related offences. However, DIRCO spokesperson Clayson Monyela cautioned that DIRCO statistics reflect only those cases ‘that are reported to our consular services’.

Compiling reliable statistics on citizens incarcerated abroad is a key piece of information-gathering. Awareness of individuals in legal difficulty allows consular services to support their citizens overseas; this includes notifying family members, providing legal advice and consular support, monitoring treatment in prisons and ensuring human-rights standards are upheld. In cases of mistreatment by police or prison authorities or other miscarriages of justice, the state can mobilize to apply diplomatic pressure on the relevant government. Awareness of the number of individuals in prison overseas is a first step in managing the complex and sensitive situations in which these individuals – who are often victims of exploitation, abuse and coercion as much as they are criminal offenders – find themselves.

Figure 4 Total number of South African citizens incarcerated abroad, February 2012–November 2019

NOTE: DIRCO does not routinely release data sets on South African citizens incarcerated abroad. The data above was released on request to the GI-TOC. It is notable that the data provided by DIRCO is selective in the years provided and there are significant monitoring gaps.

SOURCE: Department of International Relations and Cooperation, by email, 30 November 2019.

Figure 5 Number of South African citizens incarcerated abroad by region, 30 November 2019

SOURCE: Department of International Relations and Cooperation, by email, 30 November 2019.

From a domestic perspective, this is also an issue of intelligence-gathering and monitoring trends in organized crime. The individuals apprehended, and the cases built against them by foreign authorities, may provide the South African state with information about the criminal networks operating within South Africa, the recruitment strategies these networks are using and the routes that are commonly used to transport illegal goods.

However, reliable statistics for South Africans incarcerated abroad have long been difficult to come by. Some of the South African civil-society leaders and members of law enforcement who were interviewed for the Risk Bulletin raised doubts over the reliability of DIRCO’s figures, while others recounted experiences of government departments passing responsibility for this issue between each other, missing the opportunity to make effective use of this information.

‘The absence or the withholding of information in regard to South Africans locked up abroad has been a notable problem for many years,’ said Dr Marcel van der Watt, a former investigator with South Africa’s Directorate for Priority Crime Investigation, who now teaches and conducts research in the Department of Police Practice at the University of South Africa.

‘When data isn’t captured methodically and intelligently, it critically undermines any and all efforts to effectively address the issues,’ he said, adding that, when it comes to South Africans incarcerated abroad, ‘we are substantially talking about crimes committed in South Africa, where drug syndicates are giving so-called mules narcotics for smuggling across borders, embarking in South Africa. Information on South Africans locked up abroad should be valued for what it can teach us about organized crime in South Africa, yet this is not the case,’ he said.

Patricia Gerber of the NGO South Africans Locked Up in Foreign Countries said that her organization has been requesting statistics from the South African government since 2005: ‘It has proven very difficult – there have been times when DIRCO has directed us to the intergovernmental relations unit in the Correctional Services Department, and times when Correctional Services has directed us to DIRCO. We have had figures from Correctional Services and figures from DIRCO, and these have sometimes differed. For example, in 2009 DIRCO gave the official figure as 1 000, yet in response to a case I personally brought against DIRCO in 2010, Correctional Services, a respondent in that case, put the number of South Africans locked up abroad at over 1 400.’

Gerber added, ‘In the absence of a composite and accurate number of South Africans who are in prisons abroad, it is daunting to think what the consequences would be if Correctional Services is one day ordered to receive into our prisons all South Africans who are serving prison terms outside the Republic.’

In recent years, the South African government, through the Southern African Development Community (SADC), has developed and advocated the Draft Protocol on Interstate Transfer of Foreign Prisoners. The protocol is an umbrella agreement that encourages bilateral agreements between member states for the repatriation of citizens held in prisons overseas. It serves as a guide and is not intended to diminish a signatory country’s sovereignty.

‘After a 2017 SADC meeting in Botswana, the revised draft protocol was re-circulated to member states for review. Angola, Madagascar, Namibia, Lesotho and South Africa were the only member states that submitted inputs to the draft protocol, hence there has been a delay in implementing the draft protocol,’ said Brigadier Logan Maistry, deputy commissioner in the Department of Correctional Services’ intergovernmental relations unit.

Gerber founded her NGO after her son, Johann, was sentenced to nine years in Beau Bassin Central Prison in Mauritius for smuggling heroin in his stomach in 2005.

‘To the best of my knowledge, the South African government has never given, or been able to give, statistics for South Africans locked up in other African countries and the Indian Ocean islands, but I can tell you there are over 50 South Africans currently locked up in Mozambique, and at least 27 in Mauritius, 18 of them arrested in 2019 alone; four have been sentenced. I’ve often been told by officials, “You’re on the ground, the records produced by your networks are better than ours”,’ said Gerber.

John Wotherspoon is a Catholic priest who has been ministering to inmates in Hong Kong prisons, principally the Tai Lam Centre for Women and the Lai Chi Kok Correctional Institution, for 20 years. Alarmed by the high number of African nationals entering prison to serve sentences of 15 to 36 years for possession of narcotics, Wotherspoon has for a decade devoted much of his time to raising awareness about the recruitment strategies of drug syndicates and the consequences for those recruited.

Figure 6 African citizens apprehended in possession of drugs at Hong Kong airport by Hong Kong Customs and Excise, and by the Narcotics Bureau of Hong Kong Police Force, January 2010–November 2016

SOURCE: Hong Kong Customs and Excise, via Father John Wotherspoon, email correspondence, 11 December 2019.

‘The number of South Africans arrested at Hong Kong airport has radically increased in recent years,’ he said. Wotherspoon said the figure of 44 given by DIRCO for South Africans serving time in Hong Kong ‘more or less corresponds with the records of the Hong Kong Customs and Excise Department, as well as the Narcotic Bureau of Hong Kong Police Force,’ but that ‘even Hong Kong’s official figures are an imperfect representation of the reality’ (see Figure 6).

‘For example, a spike in the number of Tanzanian nationals arrested in Hong Kong airport this year does not mean there is a problem in Tanzania. In fact, the Tanzanian nationals arrested in Hong Kong airport in recent years have almost all been recruited in Ethiopia and South Africa, specifically Addis Ababa and Johannesburg,’ Wotherspoon said, adding that inmate testimony indicates that virtually all recruiting syndicates are organizations of Nigerians.

‘Nigerian syndicates operating in Ethiopia are particularly adept at recruiting Tanzanian and Kenyan women, whereas in South Africa the Nigerian syndicates have been recruiting quite a few elderly folk not of African origin, getting these individuals to leave Europe and other regions for Johannesburg, where they are duly convinced or coerced to travel with narcotics to Asian airports. The available statistics give no sense of these complex and ever evolving strategies,’ Wotherspoon added.

Van der Watt said that good data sets are just the first step in being able to understand the organized-crime dynamics behind the numbers, yet when it comes to issues of crime, whether at home or abroad, ‘the South African government is a notoriously weak keeper of records’.

‘The South African Police Service, for example, is still using the system that was in place in 1994, which has never been adapted to accommodate the malleability of crimes today, yet when you consider the quality and sophistication of the data sets put out by Statistics South Africa, there really is no excuse for the statistical failures of the police service and other departments,’ he said.

The granular information collected by Wotherspoon, and the advocacy for the rights of citizens abroad by civil-society groups such as Gerber’s, show how poor data collection is a dereliction of duty on the part of the South African government, and a missed opportunity both to support vulnerable citizens and to keep pace with the evolving strategies of criminal networks.