Placing Uganda’s response to human trafficking, and its weaknesses, in a national and regional context: The findings of the Organised Crime Index Africa.

As the previous story has discussed, Uganda faces a growing challenge in fighting human trafficking, in particular with respect to corruption derailing judicial processes and investigations into powerful individuals. Important as it is to emphasize this trend, questions remain as to how it fits into the broader picture of Uganda’s organized-crime landscape, the resilience of its institutions and the effectiveness of its response. How Uganda’s challenges related to human trafficking compare to regional dynamics is also an open question. To give some insight into these broader questions, we can make use of the findings of the ENACT 2019 Organised Crime Index Africa.1

Figure 6 Methodology underlying the scores in the Organised Crime Index Africa; for more information, see http://ocindex.net

The Index is an innovative tool designed to measure levels of organized crime in various forms as well as countries’ resilience to organized criminal activity. Figure 6 gives an overview of the indicators that together make up the Index scores on criminality and resilience, which measure countries’ political, social, economic and security frameworks. The first iteration of the Index compares all African countries that are recognized by the United Nations; it provides a comprehensive assessment across the continent using a standardized methodology and incorporating the broadest possible range of sources. It is therefore designed as a tool to provide constructive guidance to support both policymaking and policy analysis.

In terms of its overall resilience to organized crime, Uganda ranked 29th out of the 54 African countries. In terms of the detailed scores on specific aspects of Uganda’s resilience, two main patterns emerge which are relevant to the institutional response to human trafficking.

First, while Uganda has comprehensive legal frameworks in place to address organized crime, law enforcement and other institutions have not taken comprehensive action to put them into practice. Accordingly, the score given for national policies and laws (3.5 out of a possible 10) is lower than the legal framework would otherwise suggest.

This is true with respect to human trafficking. Uganda is signatory to the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and its protocol relating to human trafficking, and has reached bilateral agreements with Saudi Arabia and Jordan, both of which are significant destination countries for trafficked Ugandan citizens, on protection of migrant workers. In 2009, Uganda enacted the Prevention of Trafficking in Persons Act, its most comprehensive legislation to counter trafficking, which established the Uganda National Counter Human Trafficking Task Force. But the Task Force does not have the legal authority to compel other institutions to follow its recommendations, and, as such, the weight of the Act is diminished. A similar lack of enforcement and implementation of legal frameworks was found with respect to other criminal markets, including illegal trade in wildlife and firearms and illicit mining.

The inability of the Ugandan state to implement its legal frameworks effectively was, in turn, linked to the high prevalence of state-embedded criminal actors in key criminal markets (which scored 7.5 out of 10). This is demonstrably true for human trafficking (see the story above); it was also found by the Index to be true on a broader scale, as high-level officials have been implicated in the trade of natural resources and illicit arms, among others. On the indicator for ‘government transparency and accountability’, Uganda also scored only 2.0 out of a possible 10.

Corruption has subverted not only law enforcement but also other state-led initiatives designed to counter human trafficking. The External Employment Management System, launched by the government in 2018, was designed as an internet portal through which licensed recruitment companies could advertise pre-vetted overseas employment opportunities, enabling job-seekers to avoid exploitation and human trafficking.2 However, the system was suspended in May 2019 following allegations of abuse; officials were accused of conspiring with illegal recruitment agencies to traffic underage girls abroad.3

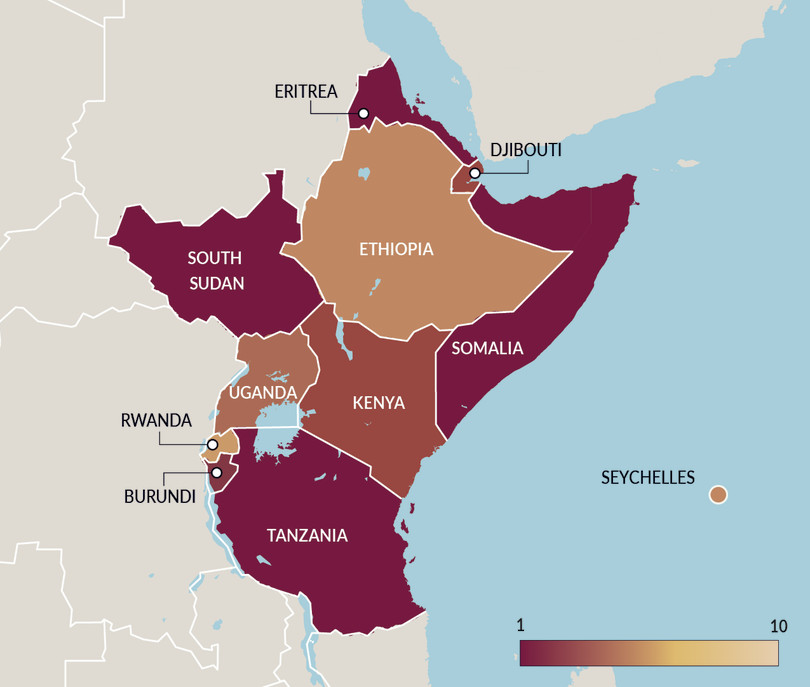

Second, non-state actors and civil-society groups have a prominent but limited role in countering organized crime, mainly centring on victim support. Uganda scored low on measures of victim support and witness protection (3.0 out of 10), which is representative of the East Africa region as a whole (see Figure 8). In fact, resilience measures in East Africa were found to be primarily focused on ‘hard’ security frameworks (such as law enforcement and territorial integrity) with less emphasis on ‘softer’ resilience measures, such as victim support and witness protection. While this is particularly true for East Africa, it is also in line with findings for the continent as a whole.

Figure 7 Organised Crime Index Africa profile for Uganda; for more information, see http://ocindex.net

Figure 8 Heatmap showing ‘victim and witness support’ scores across East Africa, from the Organized Crime Index Africa

NOTE: Victim and witness support refers to the existence of assistance provided to victims of various forms of organized crime. When states provide support mechanisms and treatment programmes for victims, citizens are able to recover more quickly from the effects of organized-criminal activities. Initiatives such as witness protection programmes are essential (and often the only way) to successfully prosecute organized criminals. As such, victim and witness support builds state resilience to organized crime. See more at https://enactafrica.org/organised-crime-index.

Ugandan civil society plays a large role in supporting victims of human trafficking, as the provisions for victim support from the state are limited. For example, civil society plays a crucial role in facilitating the return of Ugandan migrants who have been trafficked into forced labour and sexual exploitation.4 State support for civil society’s protection role is also limited.

The role of civil society in countering drug trafficking and providing support to people who use drugs is similar to that seen with respect to human trafficking. The Uganda Harm Reduction Network plays a prominent role in caring for users and advocates for their protection and rights, whereas state-led provisions are limited.5 Therefore the work of civil-society groups in filling the vital role of victim support is not unique to the sphere of human trafficking, but is a broader feature of the approach of the Ugandan state. However, while civil society plays a prominent role in victim support and rehabilitation in Uganda, civil-society groups working in the areas of governance and accountability, including journalism and activist organizations, are not afforded the same freedoms to conduct their work. These groups play a crucial role in crime prevention and investigation, as they are able to scrutinize institutions and expose instances of corruption, and campaign for preventative action to support communities affected by organized crime. A free press, for example, is a crucial part of the social framework that makes countries resilient to organized crime.

However, in Uganda, preventing and investigating crime is seen as mainly the prerogative of the state. Freedom of the press is restricted, as the Ugandan state has brought criminal charges against journalists, revokes broadcasting rights without due process and makes efforts to silence other elements of civil society, such as human-rights groups campaigning for government accountability and transparency.6

The 2019 Press Freedom Index from Reporters Without Borders ranks Uganda 125th globally, a fall of eight places from its 2018 position, citing intimidation and violence that reporters regularly face, particularly at the hands of the security services.7 This situation does not make for a conducive and secure environment in which journalists can investigate state involvement in organized crime and the activities of often violent and dangerous groups.

These two issues – the restrictions placed on civil society in Uganda and the undermining of law enforcement by high-level corruption – are interconnected. Where the space for civil society is limited, the opportunity for journalists and NGOs to investigate corruption is also curtailed, and this has been identified as a primary weakness in Uganda’s response to organized crime. The Index scores provide a tool whereby the challenges in countering human trafficking can be seen in terms of these broader, systemic issues of institutional accountability.

Notes

-

See http://ocindex.net. ↩

-

US Department of State, 2019 Trafficking in Persons Report: Uganda, www.state.gov/reports/2019-trafficking-in-persons-report-2/Uganda/2019. ↩

-

Franklin Draku, Government suspends licensing of new external labour exporters, Daily Monitor, 14 May 2019, www.monitor.co.ug/News/National/Government-suspends-licensing-new-external-labour-exporters/688334-5113894-lme64hz/index.html; Javira Ssebwami, Red flag as Bigirimana orders labour export firms vetting, PML Daily, 13 June 2019, www.pmldaily.com/news/2019/06/red-flag-as-bigirimana-orders-labour-export-firms-vetting.html. ↩

-

See for example Simon Masaba, 50 girls, women trafficked daily – police, New Vision, 30 July 2018, www.newvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1482424/girls-women-trafficked-daily-police. ↩

-

For more information on the Uganda Harm Reduction Network, see http://ugandaharmreduction.org. ↩

-

Najma Abdi, Uganda tightens clampdown on media, Human Rights Watch, 14 October 2019, www.hrw.org/news/2019/10/14/uganda-tightens-clampdown-media. ↩

-

Reporters Without Borders, 2019 World Press Freedom Index: https://rsf.org/en/ranking. ↩