Recent arrests and trials in Mozambique raise hopes in the fight against rhino poaching, but simplistic interpretations should not lead to complacency.

Mozambique has long been recognized as a hub for rhino poaching syndicates that operate from the country while targeting South Africa’s rhino population. According to reporting from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) rhino specialist group to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) conference of parties in 2019, Mozambique is a major transit state for illegal rhino horn and, in terms of the amount of horn entering the illegal market, the country is second only to South Africa. This is despite Mozambique’s native rhino population being comparatively small: there are around 30 animals, according to recent government estimates compared to South Africa’s several thousand.

On 30 September 2019, a spokesperson for the Mozambican police service announced that Lucílio Matsinhe, son of a popular Mozambican war veteran during the struggle for the country’s liberation against Portuguese colonialism, was arrested in the capital, Maputo, in possession of rhino horns. The spokesman said that their data showed Matsinhe was a ‘repeat offender’ in wildlife trafficking and the forgery of precious stones.1

The arrest was initially met with shock and surprise in Maputo and by conservationists, as the arrest of rhino traffickers, particularly those with connections in powerful political circles, is rare in Mozambique. However, on 8 October, Carlos Lopes, representative of the National Administration for the Conservation Areas (ANAC), reported that the two horns found with Matsinhe were false. Lopes said that they had been made with acrylic material, goat skin and a beer bottle.

As more details surrounding the Matsinhe case remain to be released, other cases have also emerged in recent months. On 22 August, the Maputo City Court sentenced a Chinese citizen, Pu Chiunjiang, to 15 years’ imprisonment for trafficking rhino horns; he also received a fine. According to ANAC representatives, this is the first case of a foreign national being jailed in Mozambique for wildlife crime. Chiunjiang was arrested at Maputo airport in possession of 4.2 kilograms of rhino horn. There have been several similar previous arrests of Chinese and Vietnamese nationals, but none have come to trial.2

There have also been arrests of Mozambicans in South Africa. In September 2019, two Mozambican citizens, Orlando Matuassa and Tomás Maluleque, were sentenced for 16 and 17 years, respectively, for poaching two rhinos in Limpopo National Park in Mozambique, which connects to South Africa’s Kruger National Park.3 In April, two Mozambican citizens (a father and son) were detained in South Africa. They had been found in possession of two rhino horns between Belfast and Wonderfontein, in Mpumalanga Province.

Nevertheless, reports suggest that poaching incidents in Mozambique and South Africa by Mozambican networks are in decline. According to one former poacher and current member of the Mozambican Border Guard, poaching activities are still occurring but in lower intensity: ‘The situation now is stable. We have notified very few cases of rhino poaching this year … these few cases are taking place in the small private parks and safaris in South Africa. The poachers are coming from Magude district [about 120 km from Maputo] and Massingir district, Gaza Province [about 300 km from Maputo].’ These areas neighbour South Africa.

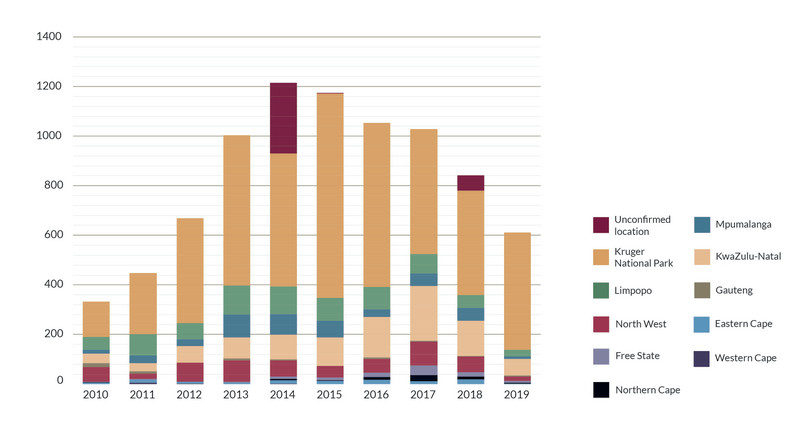

However, interpreting reported rates of rhino poaching in both Mozambique and South Africa presents some difficulties. According to the IUCN rhino specialist group, annual poaching levels in Mozambique have decreased since 2014, when 19 animals were killed, to 13 in 2015; five in 2016; four in 2017; and there had been only one case up to July 2018 (see Figure 3).4 Reporting from the PoachTracker project – an initiative of environmental journalism group Oxpeckers, which draws on official, media and crowdsourced data to collect information on poaching in South Africa – suggests that poaching in South Africa has experienced a similar decline (see Figure 4).

Figure 3 Reported incidents of rhino poaching in Mozambique, 2010–1st half 2018

SOURCE: IUCN Rhino specialist group

Figure 4 Reported incidents of rhino poaching in South Africa, 2010–2019

SOURCE: Oxpeckers, PoachTracker database: https://poachtracker.oxpeckers.org

There are debates about how to interpret this decline: while the South African Ministry of Environment readily claims the figures as a testament to the success of state anti-poaching initiatives, some conservationists have argued that, as extensive poaching in recent years has decimated the rhino population, there are simply fewer rhinos available to poach. According to environmental journalist and editor of Oxpeckers, Fiona Macleod, ‘while it is true there is a smaller population, it may well also be the case that the remaining rhinos are in fact better protected’.

How the reported decline in rhino poaching in both South Africa and Mozambique is interpreted, how this data should be interrogated, and if the recent arrests of poaching figures indicate a real swing by the Mozambican authorities to combat the issue, all remain open questions. Uncritical acceptance of a seemingly positive shift risks complacency in a context where little is being done to alleviate the drivers of poaching.